Paul Pritchard's 'Deep Play' is a must read for climbers and has inspired many of us with tales from a generation of climbers who paved the way for an increase in standards, from Sron Ulladale with Jonny Dawes to the Central Tower Of Paine in Patagonia.

His latest book 'The Mountain Path' explores a healing brain with journeys into philosophy and psychology, Tom caught up with Paul after reading...

Do you live like a Buddhist? How much of your life is now shaped by Buddhist teaching?

No. I don’t live like a Buddhist. All that chanting and all those bells would do my head in. Having said that, I do practice a form of Buddhist Romanticism each day – I go for a peaceful walk or climb. I try to get out into wild nature as much as possible.

The experience of being part of the natural world, the interconnectedness was born in my climbing life, but it was solidified in my recovery from the accident, and then Vipassana meditation, which is what Gautama Buddha practised.

Was it a long process to realise The Totem Pole accident was the best thing to happen to you?

Well, it wasn’t sudden. In fact, I became very depressed and had to be medicated during the year in hospital. I was in a wheelchair, I couldn’t talk and had uncontrollable epilepsy. Like I had a whole room full of expedition gear that I begrudgingly put up for sale.

However, it was in the physio gym I got up on the parallel bars and started to walk. It took me about 9 months to walk 100 meters with one elbow crutch. And that is when I began to realise, wow, maybe I can get a tiny part of this exciting climbers’ life back – the one I had led before. So, I slowly got back to the mountains again.

And that is when I saw the mountains through new eyes. All that struggle, all that pain, all that beauty. Now I knew what Blake was on about when he saw “eternity in a wild flower.”

Which rock and big wall routes stand out? The biggest (Asgard etc)? The worst weather (Torres del Paine?)

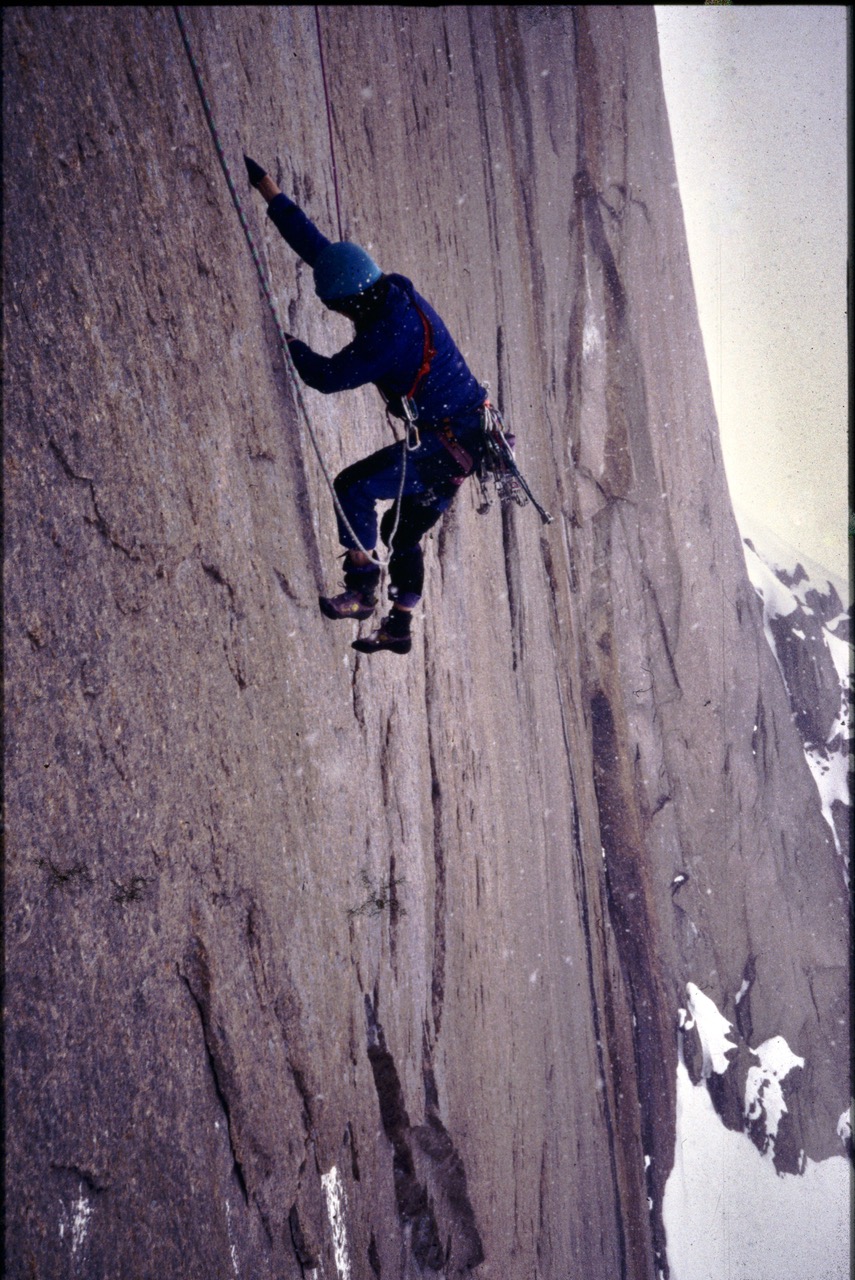

The West Face Asgard was a trip. It wasn’t the biggest wall or the longest time spent on the wall. But for sheer perfection and execution it is one that I’m very proud of. When we got there in ’94 there wasn’t any routes on the whole West Face, which was about five football fields wide and ten high. The time of year meant that it never went dark – the sun just dipped to the horizon and then began its steady climb back up.

The colours went from purple to red to orange to burnished gold. We were climbing at midnight and getting driven out of the portaledges in the afternoon by the burning sun. There was some free climbing but mostly hard aid piecing together incipient features on this huge face.

It was a great time to be climbing with so many new lines to go at. Having said that, you Tom have proved that there is infinite potential in the Himalaya.

What advice would you give to young writers? And to young climbers?

Never read other climbing books whilst you’re in the process of writing a climbing book. I have found it tends to pollute and an original voice is really hard to come by.

And for an up and coming climber - just climb for yourself, not for any sponsors or anyone pushing you to do things you don’t feel a burning desire to do.

What do you think always drives people like you (and me, I guess!) to always want more? Why did you do your cycle from Lhasa to Kathmandu, why do we always want another summit, another challenge? Why aren’t we satisfied?

Very good question that. I like to think we are searchers. Always curious about what is around the next corner or beyond the horizon. That is not to decry anyone who isn’t so. Everyone has their place in this matrix. I know I sound like a hippy, but you asked!

And climbing is the perfect medium for exploration of the self. As soon as you venture two feet off the ground on a climb you run the risk of hurting yourself or worse.

Closeness to death also has something to do with it, I think. A desire to go back to the one (I devote a whole chapter to this subject in my book). This is the ultimate paradox, we walk around acting like we have all the time in the world - like we are immortal. At the same time, we fear death like no other thing on earth. If we accept death, I mean truly accept it, then we can begin to live. And to climb ever upwards is to truly live. That’s what I think Tom.

If you could share a belay with anyone in the world, who would it be?

Well, There was this one hanging belay I had on the Red Walls of Gogarth, The Broccoli Belay, that utilised a downward pointing Knifeblade (half in and tied off) and an RP3 (bomber placement). We put Screamers on them but Bobby Drury was very worried. I think he was too heavy. I always wish Mahatma Gandhi had belayed me there, he would have been light enough…

Tell us about your new book The Mountain Path?

Well, my first book Deep Play was a really fun description of climbing culture, but as I get older, I realise that it’s much bigger; this culture. You can choose a different line and still be on the crag. You can make your own route and I guess that is what I am doing now. Deep Play was about community, my love of Llanberis and a lifestyle. I still love those days.

But The Mountain Path is about the broader community, how I integrate my climbing life daily, hourly as a parent or partner, as a migrant or a person with a disability. So, I think this book expands our understanding of what a climber’s life is.

And I hope the book broadens the way we think and talk about ‘The Mountain’ and apply this love of the mountains that we all feel into the every-day.

I’m still leading the life of a climber because those lessons I learned in the mountains, I still use use every day.

The Mountain Path is available to purchase from Vertebrate Publishing and is also available as a bundle with Deep Play