James Monypenny recounts a wild expedition to the Ladakh region of India with the late Cory Hall. The pair quested into an unknown region, with no base camp team, and set about climbing the best things they could see...

“A menacing explosion of pink and dark blue, a great symphony of rapidly changing colour, on a canvas of supernatural proportions; another truly a grandiose Himalayan sunset. Yet it was quite wasted on me. My mind was more focused on the cold. It crept in slowly, with the onset of the night, starting at my toes. Our small, poorly protected ledge, just wide enough to harbour our spooning bodies - except Cory’s lower leg dangling over the abyss - made an excellent viewing platform. From our tiny perch at 5800m, on the vast unclimbed Indian big wall, we could see our tiny speck of a tent, on the glacier seven hundred vertical meters below. In it, our sleeping equipment, food supplies and other such items that could have made the passing of the night bearable. We were castaways in an Atlantic ocean of granite. We had underestimated the mountain”.

I don't think I'm deluded; I have a plan. I also know that my plan might fail. The difficulty itself is no small part of the appeal. If success is a certainty, where is the challenge? If there is no Challenge, where is the reward? The talk with Chris Horrobin - one of the few people to have climbed in the immediate area - made the prospect of climbing Jungdung Kangri sound like an grandiose exercise in futility. Treacherous glacial moraine, loose rock, impossible climbing, mountain worshipers, and improbable permits supposedly stood in our way. However, I am still young enough to arrogantly believe that through sheer passionate will, I can bend the world to my ambition.

Prologue - Getting There

Cory and I re-united in an obscure corner of Delhi, only 12hrs after we had planned; Cory having had an unplanned detour to China. He had not changed one bit in the six months since I’d seen him last. His un-tamed hair still met his shoulders, still sporting his favourite shirt, still welding an un-bridled passion for exploration and all things climbing. Like myself, Cory had avoided the well-worn path to a routine existence. We preferred crossing the chaos of Delhi by Auto-rickshaw, rather than hiding in the modern comforts of the underground metro. The heat, and intense, busy, swerving traffic, - both bovine and mechanical in origin, that all epitomizes modern India - were a feast for the un-initiated senses.

Within 4 days we had made it to the northern state of Jammu and Kashmir. Ninety percent of the way to our mountain in distance, one percent in effort. It lay hidden in the Palzampiu valley probably no more than 60km away, near the Line of Control and the disputed border with Pakistan.

Our first obstacle was to source mules. We rented motor bikes and drove the 40km to the village of Likir that formed the gate way to the likir valley, and the southern approach to our mountain. En-route we explored a granite outcrop, reminiscent of California’s Joshua tree: a sign that there was in-fact good rock to be found, and we commenced a soloing frenzy.

After a tiresome search we located Likir's sole donkey owner, and managed to find a translator. He was an older man, small in stature, perhaps in his mid-sixties, with a weather face that told a story of a life-time spent living in a mountain environment. He was willing to join us on our useless conquest; the notion seemed to light a fire in his eye. Perhaps it was the thought of one last adventure; more likely the rupees. But alas his donkey, or any donkey for that matter, would not make it over the snow-covered pass. We would have to lay siege from the North. Which meant securing inner line permits; our next challenge. This, we were told initially, would not be possible for our desired length of stay. However being India, anything was possible, at a price.

It took an entire day to figure the existence, location and price of the local shared jeeps to the Nubra valley. Time moves differently in India. Bureaucratic hurdles, pointlessly, frustratingly, present themselves at the slightest logistical opportunity. At times it would seem that everyone’s singular motivation is the Rupee, and any fabrication would be told if it meant more money in the pocket. I longed for the simplicity of base-camp living.

Thanks to a carefully thought-out, ambitious list, shopping in the market bazaar at Diskit took a mere couple of hours, and we were soon on our way speeding in a taxi to Hundar. Although try as we might, we could not find anything that resembled porridge: the closest thing being baby food. With a shrug we bought 6 packets.

We had been told that it could be several days before mules turned up, the owner of our guesthouse seemed to think it was a worthless plight. He seemed genuine enough, yet suggested a handsome sum for porters. Experience has taught me to question. I was glad I decided to go for a wonder. My eyes lit-up at the sight -twelve, maybe fourteen mules, and their handlers, camped less than 700m from where we were staying. We went and spoke with a handler, offering him a cigarette as a baksheesh (sweetener/bribe). They were leaving tomorrow, heading to Wachan, half way to our intended base camp. At this point most people would probably not believe their luck. My friends would, no-doubt, refer to such events as "Pennyland" moments. I think we all too often wrongly attribute outcomes to luck, which is mistaken correlation of causality in my mind. Such things are merely chance, probability if you will. Probability can be predicted, chance can be measured. As a climber it is a worthy thing to realise. You minimize risks in this way. Yes, we take risks, but only when the rewards seem worthy. When you succumb to the notion that luck is a human fabrication that eases the grief of our mistakes, and justifies our good fortune, then you begin to realise that you can steer the course of your own fate. You stop wasting your time waiting to be lucky, and you create your own opportunities. And so it was we finally found our mules.

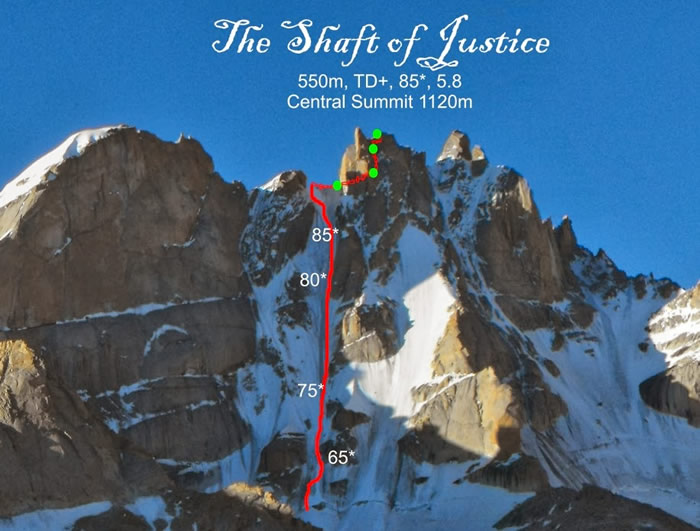

Chapter 1 - The Shaft of Justice

At 4am, when we finally emerged from our tent, after a tasty baby-food and coffee breakfast, the steep glacial basin was lit-up by the full moon, casting a long shadow over us. Our sights were set on the long couloir and central summit, to the right of the face.

Cory took the lead, and it wasn’t long before we were moving in unison, up the hard-brittle alpine ice, our lack of acclimatization immediately apparent. I took over in a passing nod, and pushed on another couple hundred meters up the eighty degree ice, until I had no gear left. The higher we moved the slower and more fatigued we became. The sun’s rays hit the corniced-top of the couloir, I felt naked and exposed as I hung from the final belay, imploring the ice to cohere. It did. But those final heavy steps were lung burning, and full of dread.

Two rock pitches brought us to the Indian head –The sharp central summit. It was less than ten meters from our grasp, but the final hardship was not giving itself up readily. We both gave it our best, but the final few meters were in-passable. I was all but ready to give-up, when Cory disappeared, down-climbing around a corner. I could tell from the rope that he had no protection and from his groans that the climbing was taxing, yet he kept moving upwards. Only a few moments later we both stood atop the airy pinnacle, taking in the breath-taking Himalayan surroundings.

Our elation, as satisfying as it was, was short lived. It was getting late in the day, and we had six hundred vertical meters to descend. Night had caught us up, and we were still making the repetitive abseils down the couloir. As I slid down our ropes I heard a sudden noise from above, before I had any time to feel emotion or horror my instinct reacted, and I swung to the right, the boulder narrowly missing me. The waves of adrenaline that surged through my veins, were quickly replaced by pangs of fear for Cory. I shouted into the darkness below: No response. My worry intensified as I continued and began to near the end of the rope, with still no sign of Cory. With rope stretch I descended a small overhang, mightily relieved to see Cory; cowering in a shower of spindrift. After a total of perhaps fifteen abseils we crossed the bergschrund, with snow falling, we stumbled back to the tent.

Life back at base camp was slow, but we occupied our time with learning to make bread and other culinary experiments, as well as reading and copious amounts of sleep. It wasn’t long before it was time to attempt the face.

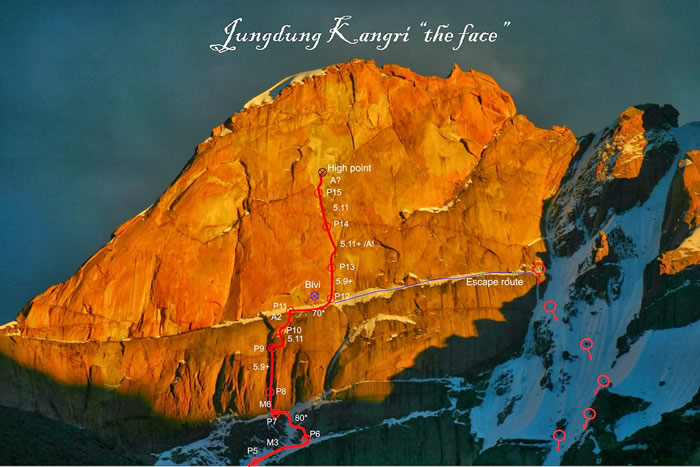

Chapter 2 - The Face

I knew it was going to be hard, but there’s no point worrying about such things; that gets you nowhere.

We decided upon a one day, lightweight alpine big-wall style approach for 'The Face' on Jungdung Kangri. As such, we had a large rack, with a double set of cams, a hand-full of pitons, aiding paraphernalia, one set of ice tools between us and a jet-boil. Deciding the difficulties would be too hard to lead with a pack, we opted for one sack between us, which the second would carry whilst jumaring. We were up and away by 4am, this time my-self in front. The initial ice pitches took far longer than we had imagined. The ice was brittle, and where we would normally move together, we were forced to pitch due to only having one set of ice tools. This also complicated matters on traversing pitches. Finally, around mid-day, we reached the rock. Cory took the lead, dispatching the initial M6 pitch in big boots. Here the wall kicked back, a maze of vertical granite rose up a further five hundred meters. Cory lead four challenging pitches, a 5.9 Crack system led to a wild belay under a large roof, followed by an exposed traverse, into a 5.10 off-width, finished with A2 aid-climbing. We reached the headwall, it was already late, snow flurries fell, we were tired, and progress upward on the complex wall seemed irrational at night. Neither of us felt prepared to give up the fight just yet, and we found a tiny perch to spend the night.

The night passes slowly. I preoccupied my mind with wiggling toes and fingers. Try as I might, I could not achieve a warm position, or sleep. At first light we began the timely process of melting snow and rehydrating our fuzzy minds. I began leading the way, and soon warmed-up. The rock was friable and the pitches difficult. On several occasions I was forced to resort to a handful of alpine and aiding tactics. We progressed slowly, eventually reaching the grey band. Here natural features gave way to difficult aid climbing. I was not convinced, and lowered to the belay. Cory displayed his usual unending positivity, and returned to my high point. At that very moment the heavens opened and a waterfall of spindrift rained down upon us. He shouted down “what d’ya think?”

Dark clouds swirled and enveloped the mountain, it was already late afternoon, further progress would undoubtedly result in another night out, without food or shelter. This was the key pitch to the face, if this went, then the route went. I desperately toiled with the decision. Eventually I concluded that the mountain was not worth our lives; “let’s live, man!”

It's perfection one moment, 'nowhere else you'd rather be,' a peak and flow of sustained upward movement. Humility and utter surrender, the next. The decision was gratified by the torrent of snow flurries that swirled the face as we executed our retreat. We inched our way, pitch after pitch, along the steep snow band that splits the headwall. Poor, spaced protection, exhaustion, dehydration and only one axe made this task seem endless. However it did serve as an effective distraction from the stomach-dropping exposure. Finally we re-joined the Shaft Of Justice, and rappelled through the night.

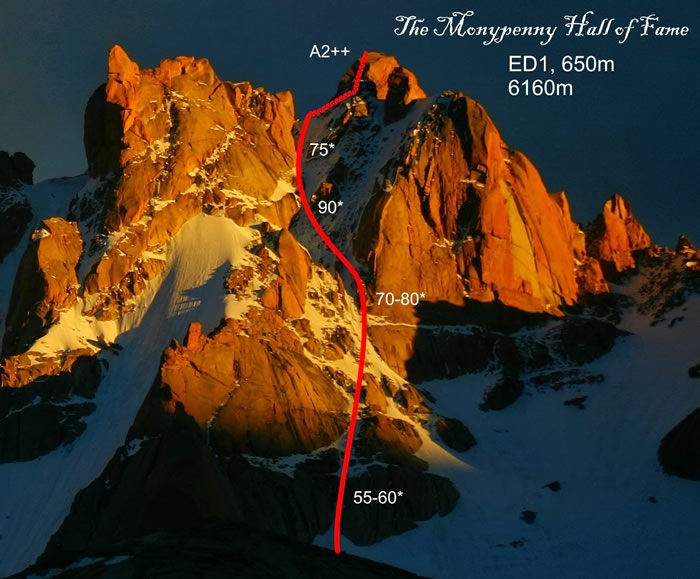

Chapter 3 - The Monypenny Hall of Fame

Had it not been for his unending positivity I would have certainly given up at this moment. One hour later I pulled, exhaustedly, onto the summit, and let out a genuine over-joyed holler. Before long we both stood precariously on our inaccessible pinnacle, smiling, giddy like school kids, in awe of our surroundings. As far as the eye could see Himalayan giants filled the vista, an abode of snow, we were visitors to the roof of the world. Cory had begun to suffer some un-known pulmonary distress, resulting in sharp chest pains & night rapidly threatened. Perhaps these factors lead to our haste.

This article first appeared on James's blog in 2013.

Read more from James Monypenny