Ben Silvestre has written a deeply thoughtful and inspiring piece, describing his year of alpine and trad climbing, complemented with some classic bouldering. The momentum gained from climbing regularly, and slowly pushing yourself further, is a special feeling, and it's a treat Ben has shared his story with us. He also talks about his new route, The Dispossessed, which is quickly becoming a new and tricky classic in the Ogwen Valley. Enjoy Ben's discussion on why we climb, the risks we take, and our exploration of the mind.

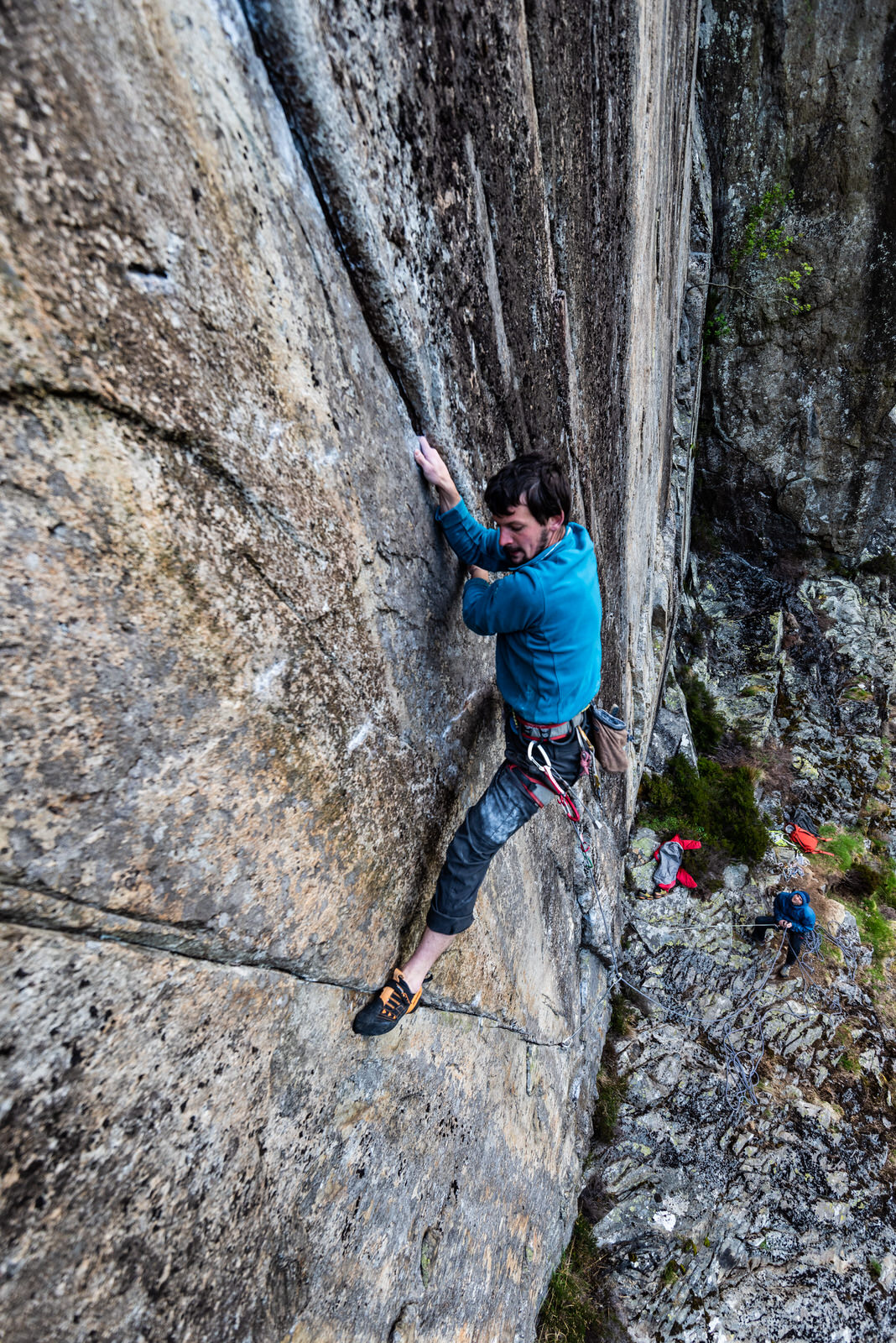

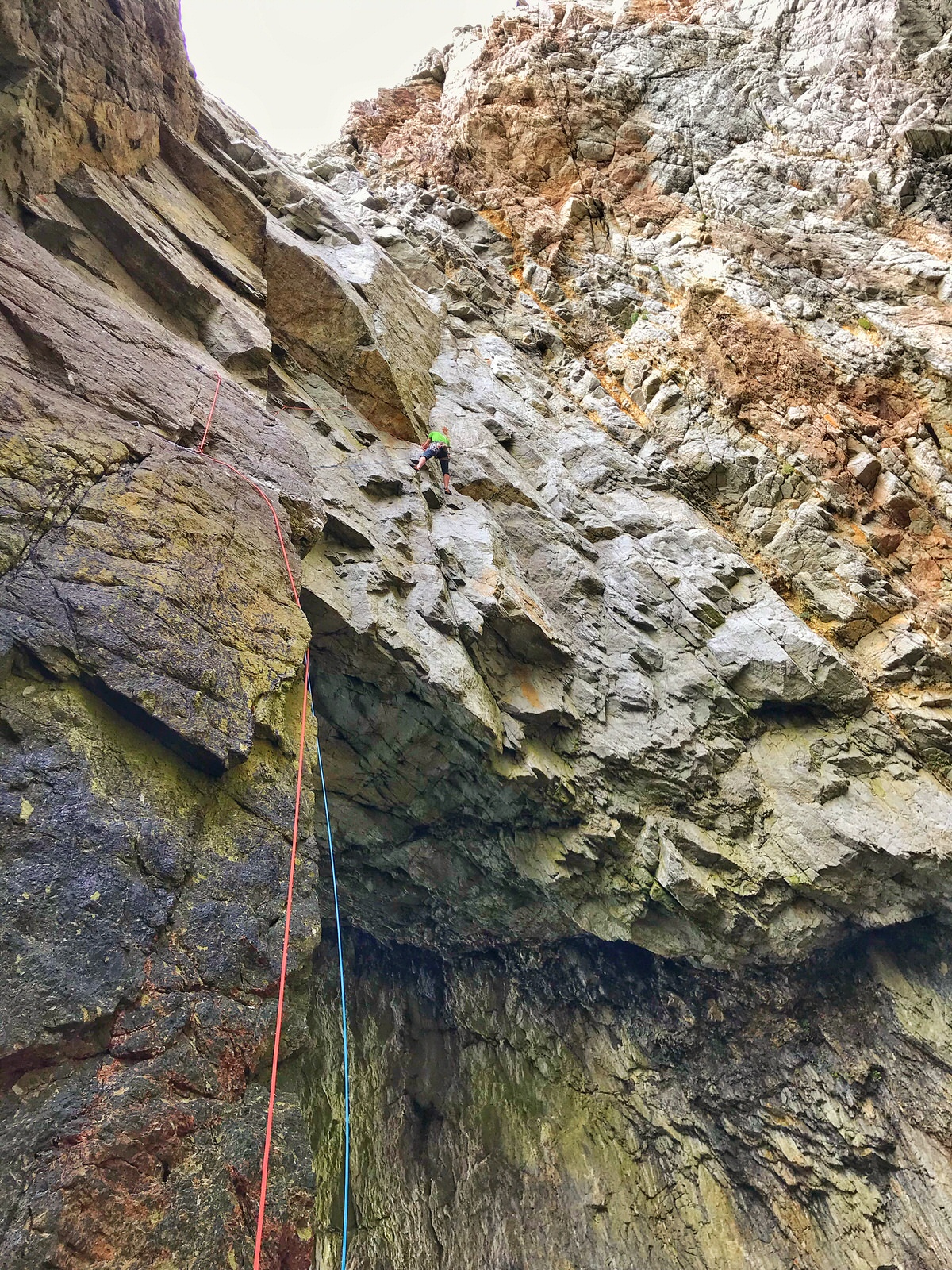

Ben eyes the next hold on his new route in the Ogwen Valley, North Wales: The Dispossessed (E7 6c). Photo: Jethro Keirnan

Onsight trad climbing is a funny business. It’s climbing in its simplest form, as it should be, without any of the nonsense which so often tarnishes the sport. When you’re not trying to push yourself, you just go outside and enjoy the movement, the landscape, the company. But simplicity isn’t always what we desire. If you want to break new ground, the key for most is incremental progress, carefully pushing your comfort zone. Could I get more pumped than this, and stay in control? Could I stay confident above fewer runners? Could I be brave enough to even try? Those are the questions we ask ourselves. Sometimes, when everything aligns, it all just feels easy. And then you know it’s time to really go for it.

My year started well, with a successful season in Patagonia. High levels of commitment on Fitzroy and Cerro Torre set the right cogs in motion, so far as the psychological side of climbing is concerned. In contrast to what is usual on those sorts of trips, we did a lot of bouldering in our down time, and it was refreshing to come back with a decent pair of arms, as well as a good head.

Of course, the brain called for a rest when we returned. I’m growing tired of the inherent danger of alpinism, uncomfortable with the selfishness of it all. So I set to work on a few boulder projects while I worked things out. Climbing the magnificent Wonderwall (7C) at Crafnant suggested that I was in better form than usual, and having relaxed my stress muscles a bit, I was soon ready to put a rope on again.

I wanted to do something different, to get familiar with a new place, far from the madding crowds of the Llanberis Pass. Tess and I recently bought a house above Bethesda, with stunning views of the Black Ladders and Llech Ddu. A traditional miners cottage, steeped in history, our home is situated in a hamlet which was a centre point for the Penrhyn quarryman strikes at the start of the 1900’s. I’m not so familiar with the Ogwen side of Snowdonia, so in conjunction with learning the history of the people who lived here, I was keen to learn more about the climbing too. Ever enthusiastic, Calum Musket was happy to show me around, and between bike rides in Braichmelyn woods, we pottered about on discreet crags which I’d never heard of.

After a few good days, Calum mentioned a project which Tim Neill had tipped him off about. Twid Turner had tried it back in the day, but never managed to lead it putting the gear in. We set off one morning, full of anticipation, and arrived at a perfectly smooth, ochre coloured wall. There were a couple of obvious lines, the right of the two looking significantly harder. We thought the crack line on the left might go without trouble, but the start looked bold and dirty so we decided to abseil in for a look. It soon became apparent that the route was significantly harder than we had anticipated, with strenuous climbing leading to a desperate crux. That first session we worked out all the moves, but we were a long way from linking them.

We returned a few days later in humid conditions, and it felt worse. Nonetheless, it was valuable time spent cleaning the route – the finger locks felt a little better each time we went up. But after that session we got distracted. Calum returned for a session with Luke Brooks, and had a good lead go, whilst I got sucked into another project elsewhere. It drifted away from my attention.

A couple of weeks later, I was ready to lead my other project, but on the day that it was meant to be, my partner cancelled. Thankfully, I had a second offer from Alex Mason – to go and try a new route with him in the Ogwen valley. Calum had mentioned that Alex knew about the crack, and I was intrigued to find out if that was his intent. Of course it was, and I headed up to the crack with him to see how he was getting on. We both struggled to make good links on a top rope, but I managed a lead go nonetheless, falling low on the route. A poor attempt, but the spell was broken, and the thing began to feel possible for me.

The following day I returned with Calum, who was keen to have another go before heading to the Alps for a summer of guiding. Calum went first and fell from the final move, millimetres from success. Shortly after I did the same, and Calum wondered whether to try again or not. After a good rest he went for it, and I could have sworn it was in the bag, but then he was airborne and that was it – he wouldn’t get another chance. Dropping him off at his house, he gave me his blessing to complete the route. If Alex hadn’t been on the scene I would have waited – I’m not in the business of stealing projects, and it had been a team effort so far. But this was too good an opportunity to pass up on.

Alex had a free afternoon the following Tuesday. It had rained hard the day before, and we were convinced that the route would be wet. But I headed up early to check, and Tess decided to come at the last minute. Surprisingly it was dry, and a cold wind promised good conditions. Warming up, the locks felt immeasurably better than they ever had done before, and I knew it was on. Sat at the bottom, I was nervous. I knew I could do it, but it would take every ounce of effort that I had. Eventually, I couldn’t sit there any longer. I’d wanted to wait for Alex, but the cold was pressing on me, and I knew that if I didn’t go soon I’d have to warm up again. This time, I arrived at the rest before the crux smoothly. The resting locks felt good, and I had a word with myself, reminding myself to dig deep. Latching the finishing jug, fully stretched out on poor footholds, it was hard to believe that I’d done it. But it was in the bag, and I was ecstatic.

Belaying Alex a couple of hours later, I was impressed at how easily he seemed to climb it, on his first lead attempt no less. He asked me what I would name it, but I wasn’t sure. Our move to Bethesda was facilitated in part by my grandfather's sister, Ogwen, and given that the route was more or less in the Ogwen valley, I thought it appropriate to honour her with the name. A batty old Welsh lady, she’s recently been deteriorating into Alzheimer's, though she deals with it incredibly well. I wanted to call it Ogwen is Cracking Up, or Ogwen has Cracked, but routes with similar names already exist.

With our move to the new house, which is a mortgage away from being ours, I’d been thinking a lot about possession. How lucky we were to have managed to buy that house, how unlucky the miners who once lived there were to be forced to submission, and often starvation, by the Lords of the Penrhyn estate. Similarly in these times, the misfortune of many people as they face the prospect of being forced away from the dream of a stable home in Britain, as the Brexit drama unfolds. How unlucky Ogwen is to be losing possession of her mental faculties. Perhaps I could honour them all with a name together.

The name came to me then, the title of a brilliant science fiction novel by Ursula le Guin – The Dispossessed. A book in which an anarchist race are forced to live on the moon of their capitalist overlords, a book which deals with what it means to have a home. To find a place with meaning, and to set roots there. To feel comfortable in one’s own mind, and retain the memories which allow us to belong. The name worked.

At the time, I also thought the name worked on another level – dispossession of Alex and Calum, who had also attempted the line. A little bit of banter, some harmless fun, but was I right? A fairly recent article on UKC, amongst a tangle of sometimes interesting, but often tenuous ideas, tried to claim that new routing, an activity which has historically been dominated by privileged white males, has always been primarily a colonialist activity, laying claim to pieces of rock.

Ben on The Dispossessed (E7 6c). Photo: Jethro Keirnan

In my initial write up for Climber magazine, I stated that the effort to make the first ascent of a safe, head pointed, single pitch climb was entirely about ownership, given that the experience changed little whether or not it was the first ascent. This was an off hand comment based on my other new routing experiences – deeply adventurous affairs in Alaska and the Himalaya. But the UKC article forced me to think about it in more detail, and I realise that I was wrong.

There is something beyond ownership which permeated the time we spent trying to climb that route. I feel it when I remember the initial sessions with Calum, when we stared at the route wide eyed and childlike. The way we carefully removed lichen and cleaned the finger locks, comparing techniques to make upwards progress as easy as possible. I feel it when I think about the sessions with Alex, mutually inspired to give the route everything we had. To be the best that we could possibly be, all the while not knowing how hard the thing actually was. And then there is the unique feeling of the first ascentionist, the feeling of grabbing the final jug, knowing full well that I was the first to do what I had done.

Of course, I own those experiences – they are mine. But they are also shared, with Calum, Alex, and Tessa. With Jethro, who took photos of us as we climbed, contributing in his way to the excitement of what happened there, without ever laying a finger on stone. We all have our place in that collection of memories, the conception of that line, we are a part of its history. Perhaps there is more in our experience than repeat ascentionists will find there.

In climbing that route, I gained the inevitable feeling of release which proceeds the fulfilment of intensely-felt desire. Does that make me a bad person? Did I feed a stereotype of white men greedily snatching first ascents from the wanting hands of the oppressed? Am I a colonial English monster for stealing the route from local Welsh climbers? Calum might agree on the latter, but in all seriousness, it didn’t feel that way to me. It felt like a good time between friends, enjoying time spent in the great outdoors. Relationships strengthened, memories gained, always pushing ourselves a little further. Certainly we didn’t harm anyone in doing what we did. But all of that feels distant now. Completion of that route left me feeling that a door had been opened – that the realm of possibility was larger than it had been before. I was ready to test myself in the real world of on sight climbing.

Ferdia Earl was the perfect companion to do so. We headed to Gogarth, where Ferdia cruised her first Main Cliff E5 – Citadel. Having climbed the route before, I opted to climb Ramadan as the second pitch, an intimidating wall which I’d been told felt nigh on E6. Jamming my hand beneath a flake on the crux, I gritted my teeth and tried to ignore the pain of a spike pressing on a nerve. In a moment of panic I almost stopped climbing, but I slapped to a good hold, and pulled myself on to the ledge above. Pins and needles coursed through my fingers, but despite the pain, I’d engaged my capacity to try hard in the face of the unknown.

A few days later, we descended into Yellow Walls. It was early still, and the greasy first pitch of The Cow put up more of a fight than it might have done, but not enough to stop Ferdia. We moved the belay down to the right, and I stared up at the final pitch of Me. Stories of a detached block after a pitch of intensely pumpy climbing had my nerves up.

'Looks perilous,' said Ferdia, and I nodded. Perilous indeed.

The initial looseness forced me into that place of perfect concentration, which doesn’t come often. An age placing a web of gear made me feel that I could go for it on the crux, and steep pulls up flakes landed me at a rest above. I thought it was in the bag, but my arms failed to soften, and my heart just wouldn’t slow. Yellow Walls – it comes with a guaranteed dose of over exposure, how could I forget? Above, I made micro movements on less than adequate holds, bridging wide at every opportunity, to take some strain from my arms. It seemed that all was lost, but I made a desperate move left, craving jugs. Thankfully what I suspected proved to be true, and I shook the pump away, wobbly block in sight. Before long I was on the top, gasping for air, and sighing with relief. I’d managed to push the margins a little further.

That afternoon, we headed to Upper Tier, and slapped our way up Strike, in a state of exhaustion. But it took us to where we wanted to be – an abseil station above Barbarossa (E6 6b). Checking the route for gear, we were pleased to discover a stainless peg, bringing the route back to it’s original state. It looked safe enough, and we decided to come back with fresher arms.

The following weekend I returned with Tess, keen for the lead. I was going to warm up on Strike, but then Tess decided she wanted a go. Tess hadn’t been too bothered by climbing lately, and a pumpy E4 would be a good lead for her if she had, but nonetheless she was up for it. I handed over the reigns enthusiastically, and was proud to see her dispatch the route in style, though not without a battle at the top. I wish I had that sort of ability, off the couch. But she was inspired, and sometimes that’s all it takes – perhaps what I said earlier about incremental progress isn’t true for everyone.

After doing Strike, I had a rest and geared up for Barbarossa. With a huge rack on my harness, I was ready for the big fight. The route is steep off the deck, and I was pumped by the time I placed the high wire, which protected the crux when the old peg was gone. The new peg was just out of reach, and I had had to make fierce moves to clip it. It looked like there were a couple of options for progress – out left to reach pockets in a couple of moves, or straight up on smaller holds for longer, but potentially less scary. I committed to the direct method, gurning my way up tiny holds, and was soon pleased to find myself at some respite and gear. But my forearms were burning, and I was only a quarter of the way up. The battle starts now, I thought. A few more technical movements landed me above the overlap, and a change of angle. Surprisingly, I could get almost all of my weight on my feet, and my arms recovered. I kept going steadily, rain threatening over at South Stack, and was shocked to find my arms getting less pumped as I made upwards progress. Soon I was at the top, pleased that both Tess and I had managed to push ourselves, and we made a hasty retreat as the first big raindrops began to fall.

Unlike Me, which had been a huge fight, Barbarossa had passed fairly steadily, and immediately I felt that I could climb something much harder. Sometimes I suffer from what I call consumer climbing, the insurmountable desire for another route always gnawing at the back of my mind. During those times, an addiction to the feeling of being pumped and exposed takes precedent over the forming of valuable experiences. But this wasn’t that feeling, this came from somewhere far less muddy – I knew with clarity that it was time to try something truly testing. My motivation was coming from the right place.

I messaged Calum asking for ideas, and was happy to see a couple of things I’d already thought of on his list. A message from Luke Brooks, asking if I was free the following Saturday, seemed to line things up. We settled on Glyder Fach, a crag I’d not been to before, and soon enough we were warmed up and stood below Kaya (E7 6b). A fairly unknown route in the wider world, but with enough of a reputation amongst locals. Better climbers than me had failed.

It took a long time to find a good enough position to place the rattling half in wire, longer still to make the moves onto the front face. I wasn’t sure if I wanted to commit, but went up for another look, and suddenly the holds felt better. I rocked around the arête, and stared the peg in the face. Moving up tenuously, I managed to clip it with a stiff quick draw Luke had given me, and hastily clipped my rope. The moment it was clipped, the feel of the route changed completely. Many more pegs lay above, and where moments before I had been climbing with a big reserve, I now felt like I could give the route everything I had.

More hard moves gained a rest, and then I was undercutting rightwards around the steepening. The climbing became markedly more strenuous, burly moves leftwards leaving me in an awkward position, where I had hoped to find something of a rest. But there was nothing, and the timer was on. Fingertips sweating, I clipped a couple more pegs, and searched for something to pull on. My feet skating on nothing, good edges barely out of reach, I was in a state of desperation. It was clear that if I didn’t move immediately, I would peel off limp, in a mess of anticlimax. So I stepped up and slapped with everything I had, screaming my way to freedom.

I was calm again when I reached the top, pleased to have fought the good fight. It had been close, and its always better when its close. But as I retrieved the gear, I realised I wouldn’t be satisfied if Luke didn’t climb the route too. He’d abseiled down it in the past, and decided that since he already had some knowledge of the route, he might as well have a look at the bold start with a rope above his head. Shorter than me, he was glad, as he had to use a much harder and less obvious sequence. But after a quick play he decided that he was ready. Some food and water, and then Luke was at the peg. But there he had a different problem from me – whereas the route had become easier for me when I clipped the peg, he suddenly had to transition from red pointing to on sighting. He made no big fuss about it though, and soon enough Luke was screaming his way to freedom too.

Ben approaching the base of Glyder Fach. Photo: Luke Brooks

Walking down, we chattered away, talking about the possibilities. I’d broken an old boundary, and a new world had opened with it. This wasn’t consumer climbing, this was a clear desire to push myself further, to see what I was capable of. To find, as John Redhead put it, 'the margins of the mind.'

There must be people out there who are never satisfied – who always want another route. Who want to conquer and claim and tell the world how good they are. There really was a time when climbing was a colonial activity, for the pride of the nation, for fame. Perhaps in some places it still is. But that’s never been what climbing is about for me, and I think I feel the same as most of my friends. I love climbing because it provides an arena in which I can push myself beyond limits which previously defined me, and I can do it alongside people who are doing the same thing. The memories formed in those moments are immensely rewarding, they enrich and vivify my existence, and I would be lost without them. Everything that is meaningful to me has come from finding those moments in different aspects of my life, within and outwith climbing. And still, after all this time, it feels like I’m only scratching the surface.

Ben at the first belay of Conan the Librarian, Gogarth, (E6 6b) after onsighting the first pitch. Photo: Tom Livingstone

Ben Silvestre is not on Facebook or Instagram. However, you can visit his website here.

You can also read about Ben's interview on Chalkbloc here.