With a foreword by Mick Fowler, if you have ever had the audacity to contemplate one of Mick’s routes (or stupidity) to actually try one, you know you’re going to be in for some chossy treats. A true aficionado of the abysmal, Mick looks for lines where none would dare to tread; summed up perfectly, I think, by multiple ‘ice’ climbs on the chalk headlands around Dover and Eastbourne in the south east of England. After continually crossing the channel and looking up at these tottering towers and gullies, it is fantastic to hear Victor recount some of the trials and tribulations of their ascents in the opening chapters, including a brief run in with the local constabulary; when both fell asleep mid route after a heavy night on the beers. ”Oh no, officer, shielding my dirty rucksack from his line of sight… I’m pretty sure they're not round here. Perhaps you should try the very far end of the cliff”. The insight into the cosmopolitan London climbing counterculture might also inspire the insipid city dweller to follow in his footsteps, particularly the photographs of Hornsey viaduct and down by ‘The Globe’.

I had first heard about Victor Saunders while reading Mick Fowler’s ‘No Easy Way’ where this book now sits, rightly, side by side on my bookshelf. Utterly dumbfounded, impressed and encouraged at their Himalayan expeditions well into their mid sixties; and with me at a tender young age of thirty can now dare to dream of possibilities in retirement.

The book has an autobiographical slant and starts in Pekan, Malaysia where Vic recounts some tales of his youth, revisiting his ama Aziza, rather than reacquainting himself with the governor of the province. Moving on in time, there are tales and adventures of various cargo vessels as Vic tries to work his way home. Having followed in these footsteps around the oceans, I can really empathise with the somewhat unglamorous duties of a ‘wiper’ and how small the ocean can make you feel at times.

Vic encapsulates well what drives many climbers into climbing: that passionate pursuit of - and dedication to - quite frequently unfathomable (to non-climbers) short term goals. “Mountains have given structure to my adult life. I suppose they have also given me purpose, though I still can’t guess what that purpose might be”. I heartily agree with that difficulty in nailing down what possesses people to climb. As well as being an ex-seafarer, we are also both of the southern England persuasion. I can relive the experience of Vic’s first traditional climbing in the Avon gorge (‘Piton route’) written within these pages. Having stopped off during a work trip, with a few hours before the drive home, I soloed this popular extravaganza, getting to the top of the second pitch just as it started to rain. I sat there for an hour and a half waiting for the top pitch to dry, or summon the bottle to carry battling upwards on polished, wet holds. Classic Rock and Ken Wilson have a lot to answer for!

This book is so much more than just about climbing. Sharing similarities with Al Alverez’s classic ‘Feeding the Rat,’ this is truly a philosophical adventure of life, with people and their relationships taking precedence. It spans bare knuckle boxing in London pubs after a Himalayan expedition, to settling disagreements with overly-avaricious porters. I think my favourite personal interaction would be Vic pretending to be asleep for an extra hour on a cold morning bivi in the high mountains, so he wouldn’t have to make the tea... before eventually cracking and getting up first anyway. The routes and destinations are also an eclectic mix, including some of the highest peaks in the world, found (to my astonishment) in Papua New Guinea of all places.

Towards the end of the book, Saunders recounts expeditions to both popular and more remote parts of the Himalaya, the most exciting of which ends up with incarceration by the Indian police after using a forbidden satellite phone to coordinate a rescue. A snowstorm triggers a localised avalanche, which blows Vic and his climbing partners across the glacier inside their tents with the force of wind driven before it. Only narrowly avoiding entombment in a crevasse and left only with enough equipment to extricate Andy Parkin, they set about a rescue mission. A final sobering section features K2. The peak has always been renowned for being a dangerous mountain, and several stories of parties coming back with fewer protagonists than they set out shows just how dangerous high-altitude mountaineering often is. But it is also testament to how mountaineers react to emergency situations.

This all leads, rather succinctly, into the introspective postscript about avalanche awareness and objective dangers in the mountains. After giving up working as an architect in London, Vic takes up guiding for a number of years while based in Chamonix. He describes in vivid detail how our choices on the hill impact our friends, clients and others around us, and never to ignore that lingering doubt. Vic himself narrowly missed being in an avalanche during what would be a routine ascent of Mont Maudit in 2012. His other growing concern, particularly in the Alps (where the height of permafrost is rising year on year) is global warming, and its impact on the mountains we cherish. More and more, rockfall is commonplace during the summer months. This was particularly evident to Vic in 2003 while guiding on the Matterhorn, resulting in all parties being helicoptered, special forces style, from above the slide.

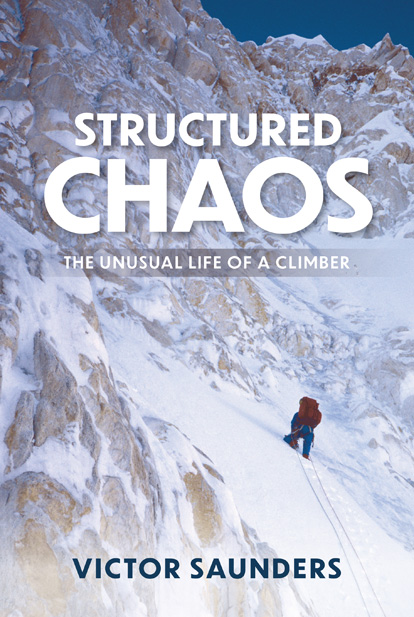

Overall, Structured Chaos is a well-written and presented autobiography with excellently chosen photographs adding colourful highlights to an interesting narrative. Vic’s enthusiasm for travel and adventure comes across in equal measure, and like myself, he clearly finds it difficult to say no to a trip. I would really recommend this to anyone interested in the genre and think Vic’s strong moral and ethical stances on mountaineering as a whole are to be revered. The poignant messages at the end support this. It’s an enjoyable, riveting and educational read.

From Structured Chaos:

Structured Chaos is Victor Saunders’ follow-up to Elusive Summits (winner of the Boardman Tasker Prize in 1990), No Place to Fall and Himalaya: The Tribulations of Vic & Mick. He reflects on his early childhood in Malaya and his first experiences of climbing as a student, and describes his progression from scaling canal-side walls in Camden to expeditions in the Himalaya and Karakoram. Following climbs on K2 and Nanga Parbat, he leaves his career as an architect and moves to Chamonix to become a mountain guide. He later makes the first ascent of Chamshen in the Saser Kangri massif, and reunites with old friend Mick Fowler to climb the north face of Sersank.

This is not just a tale of mountaineering triumphs, but also an account of rescues, tragedies and failures. Telling his story with humour and warmth, Saunders spans the decades from youthful awkwardness to concerns about age-related forgetfulness, ranging from ‘Where did I put my keys?’ to ‘Is this the right mountain?’

Structured Chaos is a testament to the value of friendship and the things that really matter in life: being in the right place at the right time with the right people, and making the most of the view.

Victor Saunders

This book is available to buy from Vertebrate Publishing.

Thanks to Alex Hallam for the review.