According to his bio at The Guardian, 'Ed Douglas is a writer and journalist with a passion for the wilder corners of the natural world.' The climbing fraternity know him as a Himalayan climber, the editor of the Alpine Journal, a climbing writer (or a writing climber?), and former editor of On The Edge magazine.

You’re editor of the Alpine Journal, run by the Alpine Club. What’s it like putting it all together?

A combination of fun and abject terror. You’re aware of the deep ocean of history beneath you as you doggy paddle away from the beach, that’s for sure. You’re also relying on the passion and interest of the contributors because they don’t get paid. I think the effort is worth it, though; there’s very little like it. Not many places you can run a big piece these days, although I’m also conscious that it’s quite a heavyweight read for some. In the next issue we’ve got pieces on all sorts, from Leonardo da Vinci’s ideas about the Alps, to the accident that galvanised French mountain rescue.

Ed during the first ascent of Xiashe north face, China. Photo: Ed Douglas collection

Your book, The Magician’s Glass, features some controversial stories in climbing. Are you drawn to write about these as a journalist, or climber, or both? Do you conclude any of them?

That book, I suppose, was a collection that featured quite a few controversies. I think if you placed them in a mainstream context they would seem pretty much standard fare in terms of digging into what’s really going on. It’s just that this no longer happens so much in British climbing. All those pieces were written for American magazines because they’re into long reads and have the time and space. Some of the people I write about in that book are outliers, even within climbing, taking immense risks and doing astonishing things. I think it’s not only fair, but also necessary, to ask questions about that process, especially if they’re doing it in the context of a public profile. If you don’t do that, then things are more likely to go awry.

What draws you to the Himalayas? How many trips have you done to this region?

Good question. A photographer I worked with there once told me I was somebody who liked the margins. It wasn’t altogether meant as a compliment. The Himalaya is somewhere on the edge of things in the minds of those who live far from the mountains, but it has its own rich and deeply complex culture that is powerfully shaped by the region’s geography. Its politics is a lot more important than many imagine and yet all that makes it into the papers is the nonsense on Everest. I’m admiring of and fascinated by the human story in the Himalaya. I’ve learned hugely there, and have the greatest respect for the resilience of people who have to cope with what the mountains throw at you, not just for a few weeks on an expedition, but through long, hard winters.

Ed on the summit slopes during the first ascent of Takphu Himal. Photo: Ed Douglas Collection

How did you start climbing, and why is mountaineering one of your passions?

I started in adolescence, which is always dangerous. It’s part of my identity as a consequence of that, and not something I can easily give up. I’m happy to say that I enjoy it as much as ever, although I’ve rarely gone climbing with the intensity of the people I write about. Mountaineering to me is deeply interesting as a subject, problematic and at the same time joyful and life affirming. I’m always amazed at how people can be doing something so involved for such powerfully different reasons. I think it’s fair to say my sympathy is with the rebels and the prophets. Performance isn’t that interesting to me, although I admire the imagination some people bring to that. I’m certainly not one for hero worship.

Do you struggle with writing an article for publication, and then the editors create a ‘clickbait’ title, which is often awkward?

I don’t struggle with that. It’s rare these days that I’ll put myself in the position where that might be an issue, and if I do then it’s a money job and I just accept it. The media is vast and complex and I basically have tried to find small niches of sanity where I can do my thing, free of too many commercial pressures. I’ve not made much money that way, but really, if you’re in outdoor journalism for the cash, you’re going to be disappointed and/or badly compromised. This is the stuff that’s supposed to be beyond consumerism. When I was a kid I found inspiration from those looking for alternative and exciting ways to live adventurously and explore the world. It was this or being a mediocre lawyer.

You must’ve enjoyed starting On the Edge magazine and Mountain Review, as well as working for other magazines? What's the future for the climbing press?

Luckily for me, I don’t have to answer that question because I don’t know how. It’s not my scene anymore. My head’s elsewhere now. When we launched On The Edge I was in the office of City Limits magazine in Manchester cutting up bromides from their typesetting machine and sticking them to boards for repro. Designing a magazine on a computer? What was that? I didn’t see that done until I worked in Istanbul on a newspaper.

As for the internet, that was still a few years off. Watching the industry you’re clinging to by your fingernails go through a revolution that strips it of most of its revenue has been quite a ride. In the outdoors, the barriers between commerce and editorial have been torn down. Marketing directors at brands drive outdoor media now, not so much editors. I like Natalie Berry at UKClimbing.com, she’s doing some good stuff. But those barriers have also come down in the minds of many climbers, who now see themselves as brands. That isn’t even a thing for youngsters today. Happily, the sort of climbing that impressed when I started is irreducible, whatever spray is being chucked around on Instagram.

High-end alpinism is a small world, perhaps smaller than it was 20 or 30 years ago, but amazing things still get done. And for the mortals, we can still go do our thing and not tell anyone. Lots of people do, it’s just not reflected in the media because there’s no coin in it. At the same time, the internet is a good way for people to share without life getting too leveraged. So swings and roundabouts. I do think there’s a gap in the market for something quite hi-falutin’, like a climbing Rouleur. The one thing I find a little sad is how the past is being let go. When I started climbing there was immense interest in the people who had gone before: they were part of your inspiration and a world to challenge too. That’s not so much the case now. The American magazines are still very plush, with a budget, but of course their agenda is different.

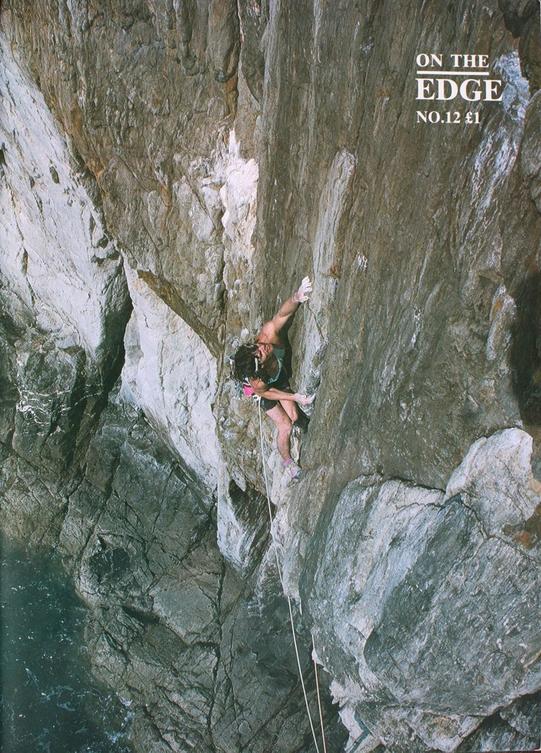

Andy Pollit on the first ascent of Skinhead Moonstomp (E6 6b), Gogarth Main Cliff, on the front cover of OTE magazine. Photo: Glenn Robbins

Andy Pollit on the first ascent of Skinhead Moonstomp (E6 6b), Gogarth Main Cliff, on the front cover of OTE magazine. Photo: Glenn Robbins

Finally, if you had to pass some time on a belay, who would you choose to spend it with?

It’s like that Fairport Convention song: Meet on the Ledge. There are a few people who have gone on ahead that I’d like to see again. Andy Fanshawe is one. I did Brown’s Eliminate at Froggatt a few weeks ago and was thinking of Paul Williams while I did it. Karen McNeill, who disappeared on Mt. Foraker [Alaska] the year after we shared a base camp in China. I’d love to have climbed with Siegfried Herford, although nobody was really belaying in those days. I daren’t mention anyone who’s alive now in case they read this.

Ed can be found online on Twitter and at Calm and Fearless.