Dave Pickford climbs, writes, and documents his travels. In climbing, Dave has established trad and sport first ascents, often adventurous and above the sea, up to E8. He’s also climbed 8b+, V11, and many 6000 metre peaks in the Greater Ranges. To date he’s climbed in more than sixty countries worldwide. Dave is a writer and editor by profession, and likes to drive very, very fast cars.

Which new routes have given the richest experiences? What are your highlights from your climbing career?

Ok… this is a big question! Climbing has given me so many extraordinary experiences it’s hard to choose a few that stand out above the rest. I’ll give it a go, though. Here’s some strong memories from a few different disciplines:

Ok… this is a big question! Climbing has given me so many extraordinary experiences it’s hard to choose a few that stand out above the rest. I’ll give it a go, though. Here’s some strong memories from a few different disciplines:

I’ll never forget my first big trad leads as a teenager. Looking down from the crux of Old Friends, the classic Stanage E4, to see all my gear fall out. And thinking ‘that wasn’t meant to happen. I better get on with this, then’. The first E6 I ever onsighted, Coronary Country at Lower Sharpnose Point in North Cornwall, also stands out. Finding a neat RP3 placement somewhere just before the crux that gave me the confidence to blast through it, then being carried up that sketchy headwall on the winds of optimism.

Making the second ascent of Infinite Gravity, Pete Oxley’s monumental 8a+ ‘adventure sport route’ at Blacker’s Hole, Swanage, in 2000 was a big deal too. I was 19 at the time, and it felt like a bit of a watershed moment. It had always been a sort of mythical route for me as I cut my teeth on the harder stuff at Swanage and Portland. I still remember being pumped out of my mind on the final traverse out left, skipping the last clip, and hyperventilating when I reached the belay. When I did it, it wasn’t a sport route. Now it’s properly bolted, but back then it was protected by 10 year old, rusting, handmade 8mm bolts that Oxley had made in his garage, various ancient pegs, all backed up by as much trad gear as I could stuff into it when I initially cleaned it.

Headpointing, whilst rewarding when it goes well, is a highly contrived form of climbing. Despite this, I wonderful memories of all of my new routes in the South West and Pembroke - the harder ones, above E7, were all done headpoint style after inspection. Wall of Spirits, my two-pitch E8 on the Great Wall at Pentire in Cornwall, is a very special climb for me personally. I remember seeing the headwall of the crux second pitch when I first climbed Eroica, the classic E3, as a fifteen year old back in the mid 1990s. And I have great memories of climbing all the classic E5s on the wall a few years later. So going back there in 2004 and firing that headwall after abseil practice was just incredible: I felt I’d left my own small contribution to one of the finest trad cliffs in England. I also did the first ascent of the left arete of that headwall, Abracadabra Arete (E7), a few years later. That’s a bit easier and less bold than Wall of Spirits, but it’s in the most awesome position right on the apex of the final Eroica groove. The history of particular routes and crags is an important aspect of climbing for me, as it is for many climbers.

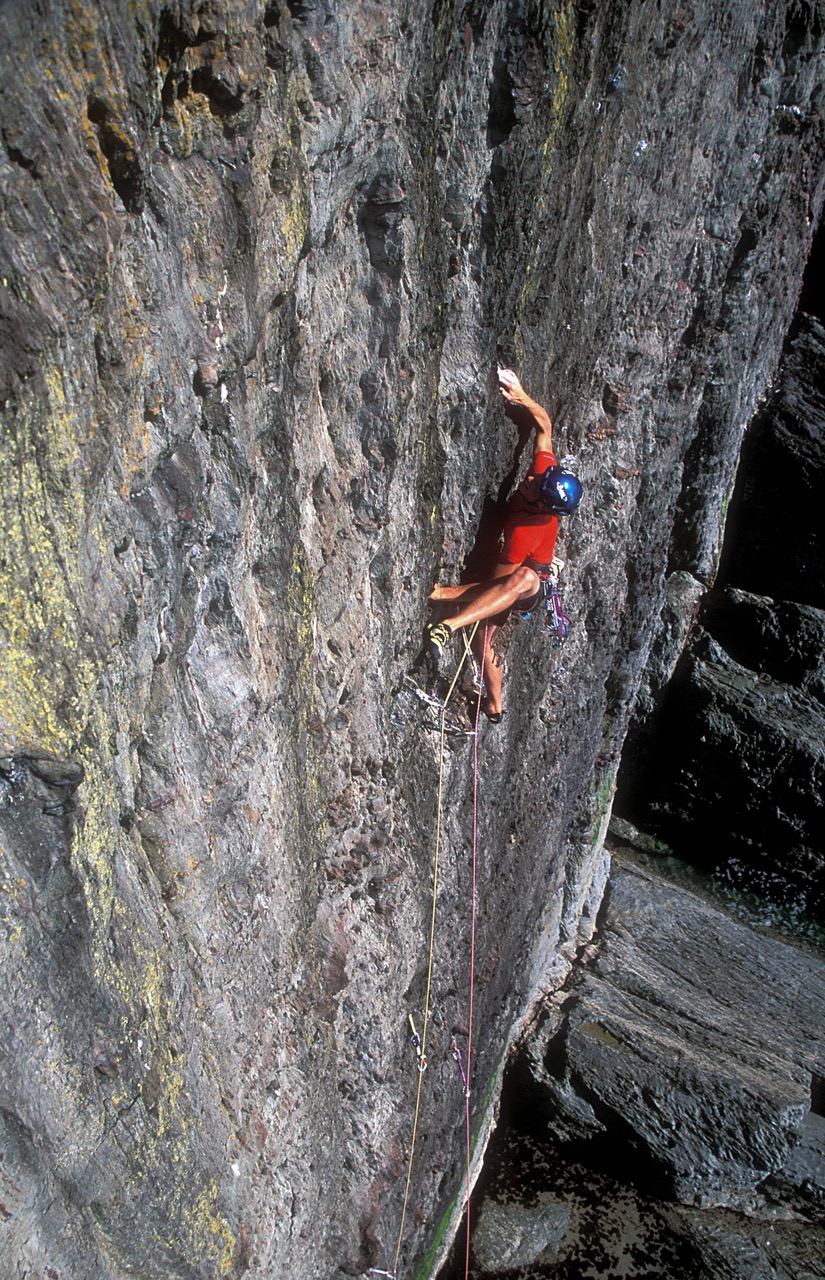

All the new routes I’ve done in Pembroke are special too. Point Blank, the big E8 at Stennis Ford, stands out because it has such fantastic climbing - it climbs very much like an endurance sport route - and it’s since become a sort of modern classic. I did the first ascent of that route 12 years ago, and it’s now had quite a few onsight ascents. I think this shows how much trad climbing standards have advanced over the last decade. When I did it in 2008, onsight ascents at that level were extremely rare.

Dave making the first ascent of the modern trad classic Point Blank (E8 6c) at Stennis Ford, Pembroke, in 2008. Photo: James Marshall

Going further afield, Kundalini Rising (V9) at Hampi in India is probably the best boulder problem I’ve ever done. It’s this gorgeous overhanging groove in a huge boulder, and whilst by no means hard by modern standards it has a really complex sequence of simply perfect crimpy moves. I did it about an hour after sunrise, I remember, to catch the cool conditions. I was alone - it was just me and the water buffalo grazing in the fields below and the swifts flitting in the morning air. Climbing alone - soloing or bouldering - can be such a powerful experience. I used to free solo a great deal when I was younger, often onsight soloing stuff up to E3-E4, and I have really special memories of that too. But I don’t like to ‘endorse’ free soloing in general, as climbing without ropes should be a very personal choice.

Geminis, the huge 8b+ at Rodellar in Spain, is probably the best sport climb I have ever done. I did it in 2010 after getting close to it the previous autumn before rain stopped play. It’s a monster route, a true king line through the heart of one of the best sport crags on the planet, Gran Boveda. And the crux is exactly where it should be, about 4 moves from the top after more than 40 metres of very steep and pumpy climbing!

In terms of big routes, the new route Sam Whittaker and I climbed in the Ak Su valley in Kyrgyzstan in 2005, From Russia With Love, is probably one of the most intense and memorable experiences from my entire climbing career. It’s a 500 metre E7 that follows the crest of a beautiful golden pillar between two much larger monoliths. We climbed it onsight with no falls - the perfect style of ascent. The crux pitch was a very poorly protected traverse, and looking back it was almost as serious for me to second as for Sam to lead. Then there were a series of pitches reminiscent of the big Gogarth E5’s that took us to the crest of the pillar. And the 10 or so ‘onsight abseils’ back down a massive overhanging dihedral system were almost as adventurous as the route itself!

Another powerful memory from my climbing life, but of a very different kind, was reaching the summit of Mentok II (6150m) in the Indian Himalaya whilst leading a Jagged Globe group in 2014. Our original objective for the expedition, Lungser Kangri, was called off by an Indian military operation so we ended up on Mentok II, a slightly lower but far less frequented mountain. It’s technically easy, but the landscape of that part of north-east Ladakh is just mind-blowing. It was perfect weather on the summit and you could see the distant peaks of the Chinese and Pakistan Karakoram like a series of frosted towers on the northern and western horizon, with the aquamarine water of Tso Mori lake glistening in the sunlight 2000 metres below.

I could go on but I’ll stop there for now. The thing that’s so great about climbing, above the activity itself, is the sheer range of experiences it offers. Climbing is such a rich mixture of sporting endeavour and visceral experience.

On the first ascent of The Nightfishing (E7 6b) on the Cheesegrater Wall at Baggy Point in 2006. Photo: Sarah Garnett

How did it feel to publish your book, The Light Elsewhere?

Publishing any book is a relief, certainly once the damn thing is out in print and you don’t have to do any more proofreading or copy checking! But yes, doing The Light Elsewhere was a very satisfying process. It’s quite a romantic book, in the sense that I tried to make it a story of a mission from the heart rather than a conventional climbing book or a conventional photo book.

Publishing any book is a relief, certainly once the damn thing is out in print and you don’t have to do any more proofreading or copy checking! But yes, doing The Light Elsewhere was a very satisfying process. It’s quite a romantic book, in the sense that I tried to make it a story of a mission from the heart rather than a conventional climbing book or a conventional photo book.

What was it like doing The Brothers Karamazov (E9 6c) in Pembroke?

It’s a big route that one. To be honest the route really intimidated me as I thought it was possible to deck out from the crux move, at least on rope stretch. So I used two belayers as the gear is quite spaced horizontally. But the actual ascent went smoothly in the end. It was inspiring taking shots of Dave Macleod a few years later when he did it in one huge 50 metre pitch - improving the original 2 pitch method.

It’s a big route that one. To be honest the route really intimidated me as I thought it was possible to deck out from the crux move, at least on rope stretch. So I used two belayers as the gear is quite spaced horizontally. But the actual ascent went smoothly in the end. It was inspiring taking shots of Dave Macleod a few years later when he did it in one huge 50 metre pitch - improving the original 2 pitch method.

You've edited several magazines - can you give us some insight into this world? [Dave was editor of Climb magazine and now BASE magazine].

Editing a high quality print magazine is a complex, sometimes stressful, occasionally frustrating but ultimately extremely rewarding process. With Climb magazine, which I edited for 7 years, Ian Parnell and I always tried to make each issue into the best magazine we could with the resources available to us (Ian was the associate editor of Climb and remains a close personal friend). That’s the most important thing - to make every issue the best it can be within the limits of editorial time and the funds you have available. I’m actually really proud of all those magazines that Ian and I edited from 2010 to 2017. Doing it as a team was important too - it would not have been possible to edit a magazine of that scope alone, and it was a lot of fun doing it with Ian. We even managed to stay good friends throughout the whole thing and not fall out with anyone (except perhaps for my own minor but widely publicised disagreement with John Redhead, but that’s another story! No hard feelings, by the way, John…)

Editing a high quality print magazine is a complex, sometimes stressful, occasionally frustrating but ultimately extremely rewarding process. With Climb magazine, which I edited for 7 years, Ian Parnell and I always tried to make each issue into the best magazine we could with the resources available to us (Ian was the associate editor of Climb and remains a close personal friend). That’s the most important thing - to make every issue the best it can be within the limits of editorial time and the funds you have available. I’m actually really proud of all those magazines that Ian and I edited from 2010 to 2017. Doing it as a team was important too - it would not have been possible to edit a magazine of that scope alone, and it was a lot of fun doing it with Ian. We even managed to stay good friends throughout the whole thing and not fall out with anyone (except perhaps for my own minor but widely publicised disagreement with John Redhead, but that’s another story! No hard feelings, by the way, John…)

Dave making the second ascent of The Satanic Verses (E8 6c) at Lower Sharpnose Point, North Cornwall, in 2000. Photo: Mark Glaister

Do you think it’s essential for people to travel and see the world at a young age?

In a nutshell yes, very much so, if you feel the urge. Over seven months, through the winter and spring of 2003-2004, I rode an old Soviet era Minsk that I bought in Hanoi around 17,000km across south-east Asia and right down through Sumatra and Java, ending up in Singapore. That trip changed my life in all sorts of ways. Then in 2005-2006 a girlfriend and I bought an Enfield Bullet 500 in Delhi and rode it around most of the Subcontinent, up to Himachal Pradesh and Kashmir, down through the Punjab and Rajastan to Goa, all the way down through Kerala to the southern tip of India then back up to Hampi. The need to travel and explore the world is one of the reasons I climb: climbing takes you to some of the most interesting, far-flung, and totally undiscovered places on Earth. I remember hearing Chris Bonington saying something similar about how climbing is such a perfect vehicle for interesting travel. That concept has not changed much since Chris was doing his big trips back in the 60s, 70s and 80s.

In a nutshell yes, very much so, if you feel the urge. Over seven months, through the winter and spring of 2003-2004, I rode an old Soviet era Minsk that I bought in Hanoi around 17,000km across south-east Asia and right down through Sumatra and Java, ending up in Singapore. That trip changed my life in all sorts of ways. Then in 2005-2006 a girlfriend and I bought an Enfield Bullet 500 in Delhi and rode it around most of the Subcontinent, up to Himachal Pradesh and Kashmir, down through the Punjab and Rajastan to Goa, all the way down through Kerala to the southern tip of India then back up to Hampi. The need to travel and explore the world is one of the reasons I climb: climbing takes you to some of the most interesting, far-flung, and totally undiscovered places on Earth. I remember hearing Chris Bonington saying something similar about how climbing is such a perfect vehicle for interesting travel. That concept has not changed much since Chris was doing his big trips back in the 60s, 70s and 80s.

There was a photo in Climb magazine of you driving a notoriously fast race car called an Ariel Atom. What was that like?

I’ve actually had two Ariel Atoms, not at the same time of course. First I had a Jackson Racing supercharged one, about 300bhp, then a Rotrex C30 supercharged one which was running over 400bhp (in a 500kg car). It was mental. You could do wheelies at 4500 RPM in 4th gear, like a drag car. I used the Atoms mainly for track days.

I’ve actually had two Ariel Atoms, not at the same time of course. First I had a Jackson Racing supercharged one, about 300bhp, then a Rotrex C30 supercharged one which was running over 400bhp (in a 500kg car). It was mental. You could do wheelies at 4500 RPM in 4th gear, like a drag car. I used the Atoms mainly for track days.

Fast cars, and other fast stuff like skiing and downhill mountain biking, are great things to do as an antidote to the general slowness of climbing and personally they are all important to me. I’ve never got into competitive motorsport, but high performance driving on a race circuit - or even a deserted Welsh B-road - really does have a lot of similarities to climbing, particularly trad climbing: the consequences if you screw up can be major with a capital M. And in the case of cars, getting a corner wrong can be very expensive.

Over the years I’ve been lucky enough to own and drive various exotic cars, including a few old air-cooled Porsche 911s, various BMW M3s, both those Ariel Atoms of course, a KTM X-Bow, a Noble M400 tuned to 550bhp (a wonderful car and very demanding to drive - as many mid-engined turbocharged cars are), and recently a manual Aston Martin V12 Vantage. The Aston was incredible, probably the best thing I have ever driven. One of the very last of the proper analogue British sports cars. I sold it a few months ago - but I already miss the animal howl of that 6 litre V12.

Piloting a Noble M400 around Silverstone GP Circuit. Photo: Dave Pickford Collection

What has enabled you to live this life, and own these cars?

If there is one aspect of climbing culture, above all others, that I find perplexing, it's this: the way many people complain about being broke, yet spend all their time climbing rather than working! There's also a strange macro-economic paradox in British climbing: whilst many dedicated climbers remain firmly on the left of the political spectrum, they don't realise (or refuse to acknowledge) the fact that without capitalism, the entire edifice of the early twenty-first Century climbing lifestyle would cease to exist. Is there much of a climbing community in North Korea, for example? I don't think so. Climbing and mountaineeering is as much a product of a capitalist society as the stock market itself.

If there is one aspect of climbing culture, above all others, that I find perplexing, it's this: the way many people complain about being broke, yet spend all their time climbing rather than working! There's also a strange macro-economic paradox in British climbing: whilst many dedicated climbers remain firmly on the left of the political spectrum, they don't realise (or refuse to acknowledge) the fact that without capitalism, the entire edifice of the early twenty-first Century climbing lifestyle would cease to exist. Is there much of a climbing community in North Korea, for example? I don't think so. Climbing and mountaineeering is as much a product of a capitalist society as the stock market itself.

I am in some ways a bit of a workaholic, I'm always doing something and I've worked really hard ever since I was a kid. Even on trips, I can't stop working on writing projects and business projects. Along with my work as an editor, writer and photographer I've built a small property business over the past decade, which is good fun in the sense that it is very different from the adventure sports arena. Rather than having a head full of dreams, it forces you to face hard commercial reality.

In terms of the cars, if you've got a good grasp of the high-end vehicle market, and you understand what you're buying, it's possible to own and drive something pretty exotic for a short time and sell it for the same money you paid for it, making the ownership a cost-neutral exercise. Crucially you should never buy anything until it's well down the depreciation curve, which usually means it needs to be at least 8 or 9 years old. So that's what I've done over the years with all the cars - drive something interesting for a few thousand miles then sell it without a loss. Obviously there's risk involved, but most of the fun things in life involve a degree of risk.

Sport climbing in a remote part of the Cederberg, SA. Photo: Ramon Marin

Finally, if you were on a belay, who would you share it with, and why?

Great question. And a tricky one. I suppose the answer depends on where the belay was, and how big the ledge was! I’ll stop there though… Purely from a climbing perspective, I’d like to share it with the Polish legend Voytek Kurtyka. He’s a fascinating figure, and a hugely accomplished climber and mountaineer. Possibly one of the greatest alpinists in history in my view. But it’s his Zen-like attitude to risk and careful, pragmatic approach to danger even in the most sketchy circumstances that appeal to me. It would be great to hear his stories of Himalayan epics first hand… particularly The Shining Wall on Gasherbrum IV with Robert Schauer back in the 80s. One of the most outrageous climbs ever done.

Great question. And a tricky one. I suppose the answer depends on where the belay was, and how big the ledge was! I’ll stop there though… Purely from a climbing perspective, I’d like to share it with the Polish legend Voytek Kurtyka. He’s a fascinating figure, and a hugely accomplished climber and mountaineer. Possibly one of the greatest alpinists in history in my view. But it’s his Zen-like attitude to risk and careful, pragmatic approach to danger even in the most sketchy circumstances that appeal to me. It would be great to hear his stories of Himalayan epics first hand… particularly The Shining Wall on Gasherbrum IV with Robert Schauer back in the 80s. One of the most outrageous climbs ever done.

On the descent from the summit icefields of Mentok II (6150m) in the Tso Mori region of eastern Ladakh, Indian Himalaya. Photo: Dave Pickford Collection

Dave Pickford is the editor of BASE magazine, a free adventure sports quarterly. You can find out more about Dave here, or BASE magazine here.