Andy Kirkpatrick is one of the best known climbers in the UK with a long history of difficult alpine and big wall routes, often in remote and cold locations. Andy's books range from award winning classics such as Psychovertical and Cold Wars through to instruction manuals on big walling, all are recommended reading.

Here's the interview with Andy chatting to Tom Livingstone...

Do you feel that aid climbing is slightly unknown in the UK - it's obviously big in the US, but there's not much understanding about it here?

It's funny, but I'm often pigeon-holed as an 'aid climber', but only really do one wall a year, and think of myself as more of an alpinist really, and always considered aid climbing as a central part of trying to do really hard alpine climbs, stuff that required a high level of skill in free, mixed, ice, aid, survival etc.

My heroes when I started were the Poles, Russians and Slovenians, who were climbing routes that have rarely been bettered in terms of pure gnarliness. In the UK you had Paul Pritchard, Noel Crain and Adam Wainwright, plus Twid and others, doing hard aid climbs in the US, Baffin and Patagonia, and people often forget Doug Scott began as a big wall climber really.

When I climbed the Dru Couloir as my third alpine route I was really slow on the aid pitch (there was also a major rescue of two climbers going on at the time), and decided to be a better alpinist - to be Hull's Silvo Karo - I had to learn to aid. So the following year I went out to Yosemite and climbed the Shield and PO wall. Alpine climbers often go on about being committed etc, but I think climbing a hard, dangerous wall, redefines a lot of things in an alpine climbers head. It also gives you a great work ethic and an ability to break down very large problems into their component parts.

How do you feel about your hard aid routes, on reflection? Do they give contented memories, or are they more 'battles' which you feel glad to have finished with?

I guess it's like Mick Fowler says, that the best routes are the routes you either only just fail on, or only just succeed at; a big hard wall often an unrelenting battle with fear and anxiety, self-doubt, and physical and emotional exhaustion. An alpine route will hopefully last only one or two bivvies, or be done in a day, while a harder big wall could last a week, two weeks, maybe even longer, and so really they're not the same sport (I think I've said to James Mchaffie - who always gives me a hard time - that he's a surfer and I'm a cave diver, and that neither of us can do what the other can do).

Steve House called this style of big wall climbing, what the Russians did on Makalu and K2 for example, as guaranteed outcome climbing, which is a little disingenuous when you consider how many people fail to climb their first big wall (and so fail to progress onto harder walls). By the time you rock up below a 2000 metre big wall at high altitude or in Patagonia or Antarctica, you'll have a very broad skill set, a skill set that perhaps has more depth in terms of survival and 'overcomeption' than someone who's been rock climbing in the high Sierras and fancies their chances on Fitzroy.

In terms of guarantees, the most significant factor in success compared to alpine climbing is weather is less of a factor, as you have the means to survive, but really anything that requires that much work, for that long, often translates to success. So the memories often have little joy, but really of hard work well done (the joy comes in the afterglow).

What are your lasting memories from bigger routes like the Lafaille, Troll Wall, or Patagonia? Or are they all very different memories?

It's like asking what your memories are of ex-lovers, wives and girlfriends, in that the greater the distance from that relationship (if you're on the Troll wall for 14 days in winter it's not a one night stand), the fonder the memories, the hurt of it all fading into the background (but really, you can't cope with ever seeing them again, as it might all come rushing back).

In Cold Wars, you seem to be in some conflict between family and climbing. Have things resolved themselves, or is it always a hard balance (family and climbing)?

This morning I was asked if I wanted to join a small team to try and climb K2 in Winter. At the moment I'm living in the Middle East (or Crematoria as I call it), and will probably be having more kids with the woman I love (starting adult life all over again).

I make a living doing what I love, have no debt, and everything is as perfect as it could be. But then you get an email like that. All I think of is how it could derail my life, because as soon as you say yes, that's all I'll think of, train and plan for over the next two or three years, and nothing else. And if I say no? Well, it's all I'll think about. It turns the pleasure of each moment you're alive into just the hard metallic tick of a clock; you fritter away the real value of your life on the promise of something not worth the cost.

What advice can you give to other climbers wanting to get more into public speaking (I'm partly asking from a personal perspective)

People often say to me "Oh I'm retiring, I might start writing", which I think is a little disingenuous to writers, as 'writing', unless it's just for yourself, is like saying 'I'm retiring, I might take up heart surgery". Yes, you can hack away with a knife, maybe even be pretty good at stitches, or keeping your scalpel clean, but it takes decades to get close putting it all together, which has nothing to do with writing (just as heart surgery is more than just cutting), but of all the aspects, the biggest one is how to make it self funding.

Public speaking is the same, in that the speaking part is probably the easy part, and if you watch Tommy Caldwell on TED, you can see how polished you can become, which is about performance. But the real art is somehow remaining yourself, presenting what you want to say, not what people want/expect you to say, and so take people on an actual journey, not just an exercise.

All of my income outside of writing comes from touring in theatres every two or three years, and now I'm at the level of a solid comedian who is not on the TV (selling 300 - 500 tickets a show, and doing about 25 to 30 gigs in a tour). But this required decades of hard work, talking at universities where no one came, in schools, and pubs and climbing clubs. I once did a talk for Cotswolds where only three people turned up (although none turned up for Tim Emmet the following week!). I think around 2002 I did an awful run of talks with university clubs, and it was just terrible, and I thought 'I either need to pack this in, or move up a level'.

I identified that my problem was my audience was climbers, who are the most unreliable and tight arsed customers you could ever wish for, and a group you could not hang a career or income on. And so I decided I had to ignore climbers all together, and focus on real people, the people who watch Bear Grylls and Ray Mears and Ben Fogle etc, as much of what they do is make-believe, where my stuff was real, and there was a lot of it.

I also removed the stuff that climbers - who are nerds and extremists - want, the tedious detail of what rubber did you have on your boots, and focus more on the human and universal elements, of facing down your doubt in yourself, balancing the individual desires with security, responsibility etc. I started a company called Speakers from the Edge, which then used what I'd learned, taking outdoor people (not just climbers), and moving them into theatres and packaging them in a way that made them more accessible. Through that process, I got to understand how marketing works, understood the use of social media (before it was a thing), and loads of other tiny things that make speaking pay. And so, when climbers often get in touch about doing speaking work, mainly due to having a short term injury, I ask "how long have you got?"

Some of your writing causes controversy. Do you think it's important to say or write what you believe, even if it's going to cause upset?

The fact the answer I give below will upset people is maybe why it's worth writing in the first place, but I think we're living in an increasingly conformist times; somehow a trick has been pulled, where people with ultra-conservative, conformist and puritanical (even religious) views are totally unaware of how irrational they are.

For example, people who talked about polarization tend to hold very polarized viewpoints (they tend to mean 'why don't other people think like me?'), while people who talk about racism and inequality tend to be incredibly racist and lead a life that's not equal at all (just as suicide and depression is a western indulgence, so is an obsession with poverty and inequality).

If you read the above and it makes you angry, then what's wrong with you? Do you take this as a personal attack, that you suffer from depression and don't view it as an 'indulgence'? Well, maybe you've never thought about in the way I have, and perhaps this way of thinking is why I don't medicate myself to feel normal.

I think the freedom to think and say what you think - even if it's wrong - is a core human right, as it allows us to work through ideas that could be important for ourselves and society at large. But at the moment to tell the truth somehow makes you a contrarian, alt-right, a deplorable, a heretic. When you tell someone only 8% of climate emissions come from Europe or that of 40,000 gun deaths in America, two thirds are suicides (and 85% are men), this information is somehow dirty, dangerous, when really it's data that's missing out of most peoples computations of reality (which I believe leads directly to hate, depression, poverty and general discombobulation).

As a writer, to be a real writer, you have to be fearless in your dealings with the world, you must understand the irrational, learn to love the racists, the bigots, the narrow-minded, those without a doubt and only faith, otherwise you risk becoming just like them. You must always be an outsider looking in, saying what no one else is willing to say, even if it means you'll lose most of your fans and readers, get dropped by brands, lose speaking work, even lose friends you've known all your life. In terms of me the writer and me the sponsored climber, well I had to give up working for Montane (it was my job), which was my primary source of regular income, as people would attack me via them, the idea in these things always correctional (think like us, or else you will suffer, or attack anyone connected to you). When people do this kind of thing, they think money and security (and free sexy kit) will trump free expression, but there's that working-class Hull militant streak (you see it in John Redhead as well, another Hull climber), which is not so easily bought off.

Also, self-destruction is always transformity, so it's a gift really. People have contacted almost everyone I've worked for trying to have me blacklisted as a non-person (such things sound overblown until they happen to you). The fact people think I'm just trolling is what makes me sad, as to me - just as I want to help people be safer in the mountains - I want people to be safer in their heads, as I see psychosis all around me. When I wrote two and a half years ago that the whole Russian collusion thing is taking the minds of intelligent and rational people, and cynically putting them through a mangler, making such people just dumb robots or dogs that bark on command, why am I viewed as having 'dangerous viewpoints' or asked to 'just stick to writing about what you know'.

But like a Russian dissident who only tells the truth through science fiction, this day has come for me, and on the surface (partly due to where I live), I'm going straight, and only writing within the boundaries set for me by society.

You've mentioned above ‘People have contacted almost everyone I've worked for trying to have me blacklisted as a non-person.’ can you expand on that?

Most people in the UK seem to view me as being alt-right (whatever that is), racist, anti immigration, Islamophobic, and someone who has dangerous viewpoints, and whenever anyone defends me, in anyway, they will always begin with ‘I don’t agree with everything he says...’. I’ve had people say they’d boycott my books due to my politics, which is odd, as I only ever voted labour when I lived in the UK, grew up with refugees, live in a Muslim country, and have always been very socially responsible.

Such things are part of the course of just saying what you think, and there’s an aspect tied to jealously (I suffered the same feelings towards other people), but there is also an aspect of the tyranny by the minority.

What I write very much reflects not living in the UK, spending three months a year in the US, living in Ireland for a few years, and that people outside of the UK, who are not climbers, see things very differently. But this turned pretty dark as there was some campaign to have me fired or lose support or work etc, from magazines I worked for, brands, the BMC (they would not put money into Jen’s Psycho Vertical film, again, I’m working with a female film maker yet I’m a misogynist etc).

It came to a head with Montane with them getting a load of shit about me being Islamophobic (look it up on UKC), with even people who worked for UKC joining in, a pretty sad state of affairs when you’d imagine climbers to be intelligent, open minded and rational. The saddest thing is the number of private messages I get (I mainly wrote about how we view the world, about hard data, not about Trump or Brexit and all that shite), that people think I’m brave for being honest, but they themselves don’t feel so brave to speak what they feel is the truth. There are aspects of the UK I don’t really recognize anymore, like something out of 'Invasion Of The Body Snatchers', where everyone I know has been replicated. I guess I genuinely believe one day all these people are going to return to being humans again, to get a grip, that people are living a rapidly unwinding false reality, that this real life role playing is about to come to an end. We will see.

Have people actually said to your sponsors, “why are you sponsoring him?”

It’s funny, but I’ve worked for Patagonia (international gear tester) in the 90s, and been a Patagonia athlete twice, worked for Berghaus and Montane, but always been the one to leave my sponsor, but never to go to another one, the reason being I don’t think I’m good enough, that I’m not a real climber. I’m just a hustler. But maybe it’s worth understanding the game in that it has little to do with how good you feel you are, it’s how good people think you are, how you promote what you do. Just think of Bear Grylls, who climbed Everest sometime in the 90’s (I sold him his One Sport boots), and has been selling that story ever since.

If people considered the amount of promotion climbers do for a brand, which is marketing gold, as it’s hardcore and real, when set beside some gear or even a few thousand quid, climbers must be crazy to sell themselves so easy.

I find this level of aggression surprising, as firstly I’d say your sponsorship is justified , and secondly just as you say, it sounds overblown but I wouldn’t be psyched if it happened to me.

I actually enjoy the aggression, as I need friction in my life to create a spark, and don’t do passive states well. It’s very healthy to not put followers and hits before principles, to call bullshit on something and not worry about offending someone. The need to be loved and to fit in is very dangerous, and so to seek to be hated is liberating, when someone tells you ‘to stick to what you know’ to not agree and say 's'sorry, I will try harder’ but just tell them to go fuck themselves.

You also mention above, ’My heroes when I started were the Poles, Russians and Slovenians.’ Who are the people you are impressed by now? Older or younger, who do you think is worth noting?

Alpinism is dying, it’s heading towards cave diving status, and people have no stomach for it anymore (just look at how many people even climb on mountain crags in the UK these days). We’ve both had a lot of friends, people who we know and have met who’ve died, so I do really care about its passing, as it not meant to be a mass participation sport, but only for the warped and the eccentric and those looking to make a name (usually posthumously). What’s sad and the surprising thing is not the number of great climbers who have died but the number who are still alive and so I suppose I respect the survivors more than the suicidal and the delusional, people like Jim Donini, Conrad Anker, Greg Child, Silvo Karo, Doug Scott, people who have not placed all their money on climbing, but other things as well (so not Fred Becky!).

You also say, ‘the best routes are the routes you either only just fail on, or only just succeed at.’ Which of your routes fit this category?

I’ve been on loads of trips that didn’t go anywhere, and I think I did six trips to Patagonia in Winter, been to Alaska twice (again, in winter), and loads of stupid places with stupid people. I tried the grand traverse on Mount Kenya with Vanessa last year, a route that never gets done, and we had three bivvys in crap weather and the worst rock you can imagine, and failed to get to the top. She couldn't understand why we didn’t just try the easy route, which we’d have done, but I just said that’s not the point - to just get to the top - but to make the top as far from you as you can. Alex Huber said I self sabotage myself, I climb in winter, I don’t get fit, I climb with people with no experience, I solo routes etc, but for me I just like to make things hard - I like the friction. So routes that only just got climbed? The Parkin route on Meromoz in winter or the new route we did on Ulvertanna were very close run things, while bailing 35 metres from the top of the Troll is probably my proudest non ascent (going back in winter to go all the way up for that 35 metres was a total waste of time).

Finally, because I forgot to originally include it, if you had to share a bivy with someone, who would it be?

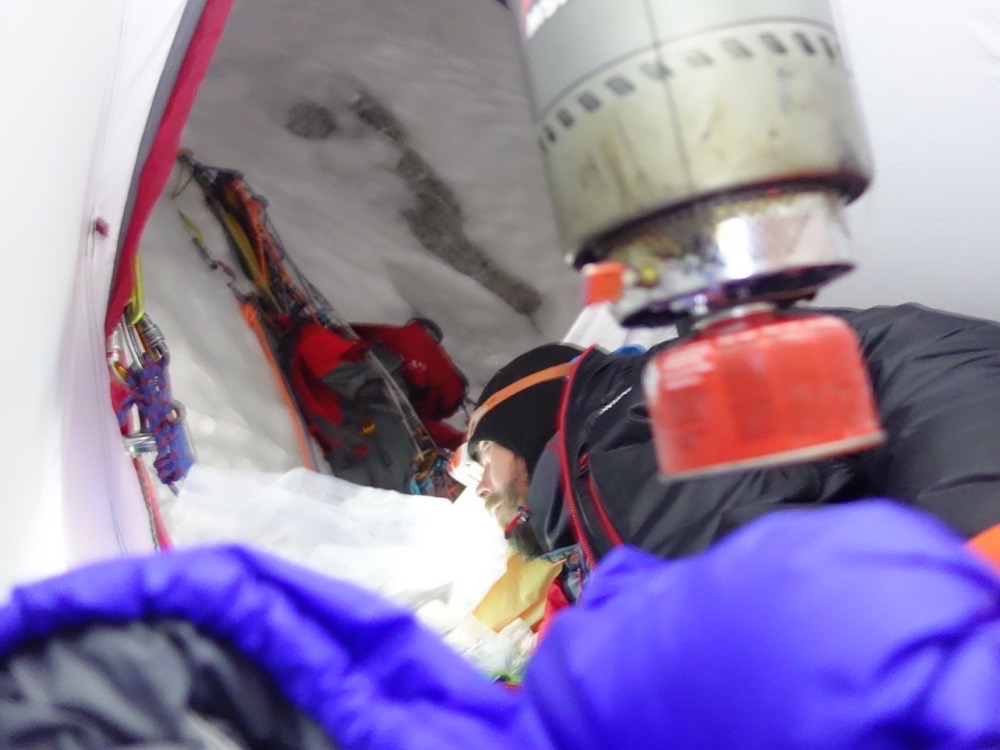

I have to say it would be my wife, otherwise she’d kill me, although we did spent 6 weeks on Denali this winter in the same sleeping bag for about 14 hours a day! But really, a good bivvy partner is someone you’re comfortable not talking to and who doesn’t tell you you snore (and you reply in kind).

You can read more from Andy on his (self built) blog and follow him on Facebook and Instagram.

Andy is sponsored by Petzl and La Sportiva