Steve Long is a climber, IFMGA Mountain Guide and President of the UIAA's (International Climbing and Mountaineering Federation) Training Panel. Based in North Wales, he still climbs and puts up new routes. In this interview, we hear some of Steve's highlights in climbing, as well as a few entertaining adventures and mishaps.

Firstly, what do you do for work? What’s your current role for the International Climbing and Mountaineering Federation (UIAA)?

My job: I’m a freelance International Mountain Guide, but most of my work is better described as coaching or mentoring. It’s very varied, ranging from safety work for filming, advising mountaineering federations about training programmes for leaders and instructors, quality assurance for Mountain Training UK and technical editor for the mountaineering associations’ quarterly internal magazine “Professional Mountaineer”. I also work on some higher level courses such as International Mountain Leader and British Mountain Guide training and assessment courses. In recent years I have cut back on professional work, in order to free up time for training projects in countries that want to develop or improve their training programmes - also to have more time to follow my two great passions: climbing and gardening. In 2006 I became chair of the training working group of the International Climbing and Mountaineering Federation (UIAA) - this role has developed into what is now more grandiosely called President of the Training Panel and has become my main driving passion, professionally speaking.

My job: I’m a freelance International Mountain Guide, but most of my work is better described as coaching or mentoring. It’s very varied, ranging from safety work for filming, advising mountaineering federations about training programmes for leaders and instructors, quality assurance for Mountain Training UK and technical editor for the mountaineering associations’ quarterly internal magazine “Professional Mountaineer”. I also work on some higher level courses such as International Mountain Leader and British Mountain Guide training and assessment courses. In recent years I have cut back on professional work, in order to free up time for training projects in countries that want to develop or improve their training programmes - also to have more time to follow my two great passions: climbing and gardening. In 2006 I became chair of the training working group of the International Climbing and Mountaineering Federation (UIAA) - this role has developed into what is now more grandiosely called President of the Training Panel and has become my main driving passion, professionally speaking.

Staff and students on one of the Nepali training courses, with Steve (far right). Photo: Steve Long Collection

Staff and students on one of the Nepali training courses, with Steve (far right). Photo: Steve Long CollectionIt seems you get to travel to exciting places for work as well. Any highlights from the last few places?

In my role within the UIAA, I get invited to help train leaders and coaches all over the world. Recently we have introduced a further international level of training for personal skills development i.e. good practice. These initiatives provide syllabi and other guidance for federations that cascade down to their accredited instructors, coaches and guides. The aim is to help trainers deliver courses that help "newbies” get off to a good start in mountain activities such as hiking and climbing.

Last year, for example we helped Ladakh [India], Mongolia, and Kenya develop training programmes which hopefully will lead to fully fledged qualifications in these countries. The model for these projects is the Mountain Leader qualification that we helped the Nepal Mountaineering Association (the official national federation) to develop. This is now a self-sustaining qualification delivered by Nepali trainers, two of whom joined myself and several other trainers for the project in Ladakh.

All of our projects have multi-national trainers, so we have to work collaboratively to reach agreement on specific techniques that we will be teaching. I prefer to stay off-programme and work as a floating director but this isn’t always possible, due to financial constraints. These projects are voluntary, but living and working with the locals is a big enough reward in itself. So much so that I have mainly abandoned climbing expeditions these days. It might sound odd, but the logistics involved, the teamwork required, and the spirit of camaraderie with local mountain enthusiasts gives me many of the emotional and spiritual highs that I gain from mountaineering expeditions, but without that slight feeling of anti-climax that can kick in after achieving a goal: I often think of the title of Lionel Terray’s book “Conquistador’s of the Useless” and feel privileged to have found an opportunity to channel my love of travel and mountains into something that feels useful: teachers rather that tourists.

Don’t get me wrong, I still love climbing, and being in the unique zone that exists when the next few moves are all that really matters in my world - at that moment - but these training initiatives certainly help me to feel more connected to the mountains and their communities, and are therefore richly rewarding. There are more tangible rewards as well, such as grabbing a day off between courses to climb with colleagues or locals.

Each training project has been a wonderful experience in its own way, so its hard to pick highlights. However, a few memories do stand out: crossing the Ganje La (pass) in winter with a team of 20 Nepalis, hiking into Zanskar on a frozen river with a team of Swiss doctors to train a volunteer rescue team and nurses, climbing “Lionheart” and “Jihad” on days off in the Wadi Rum, trekking into the fabled city of Petra by moonlight, and most recently galloping across the Mongolian steppes with some nomads!

The most recent project, just before the Coronavirus-19 lockdown kicked in, was a course for mountain hiking leaders in the area known as the Western Ghats near Mumbai, a region known locally as Sahyadri. We were really inspired by the love that the local leaders showed for this region, largely ignored by global tourism but an increasingly popular destination for city dwellers from Mumbai and Pune. One of the toughest challenges was delivering a back-to-back series of courses from Shipton’s Camp on Mount Kenya. We were living at 4000m, with unseasonably cold wet conditions for a fortnight - again the enthusiasm of the local guides was truly humbling and motivated us to overcome the difficulties presented by the weather and lack of electricity.

As I mentioned above, the training projects provide many of the spiritual aspects that drew me to climbing in the first place, and over four decades, I’ve visited most of the places that were at the top of my bucket list - though there are exceptions such as Baffin Island and Greenland. The North Face of the Eiger is still on my list.

But I feel that the “golden age” of travel is over now, unless we are collectively able to reduce our carbon footprint very dramatically. The reactions to the CV-19 crisis convinces me that humans are collectively incapable of reacting to advance warnings that involve painful sacrifices until the consequences of inactivity are irrefutable and immediate.

This makes it difficult for climbers: I strongly believe that exploratory climbing and mountaineering embody important human aspirations to transcend perceived limitations and boundaries, but at what point does the carbon footprint that this entails undermine the journey? Back in the day we were innocent of the collective toll our travels contributed to global warming. On the other hand, we could throw out the baby with the bath water, and our empty seat on the plane will be used for more mundane pursuits.

I don’t have an answer to this but my personal compromise satisfies my conscience: most of my travel is attached to hand’s on delivery that couldn’t be delegated to a local. Now that we have a global team we are increasing able to deploy experts who live closer to the training site, so as our impact has expanded, our carbon footprint has stabilised. I don’t know what the post-lockdown world will look like though. Several of our sponsors, and many of the candidates will face huge financial losses, possibly career-changing ones. On the other hand, worldwide the demand for adventure and exploring nature will increase as more communities trade farming and transhumance for city life and find their souls sickened for connection to the earth as a by-product. So I believe that the demand for training and coaching will increase, and we will find new ways to deliver it.

The most recent project, just before the Coronavirus-19 lockdown kicked in, was a course for mountain hiking leaders in the area known as the Western Ghats near Mumbai, a region known locally as Sahyadri. We were really inspired by the love that the local leaders showed for this region, largely ignored by global tourism but an increasingly popular destination for city dwellers from Mumbai and Pune. One of the toughest challenges was delivering a back-to-back series of courses from Shipton’s Camp on Mount Kenya. We were living at 4000m, with unseasonably cold wet conditions for a fortnight - again the enthusiasm of the local guides was truly humbling and motivated us to overcome the difficulties presented by the weather and lack of electricity.

As I mentioned above, the training projects provide many of the spiritual aspects that drew me to climbing in the first place, and over four decades, I’ve visited most of the places that were at the top of my bucket list - though there are exceptions such as Baffin Island and Greenland. The North Face of the Eiger is still on my list.

But I feel that the “golden age” of travel is over now, unless we are collectively able to reduce our carbon footprint very dramatically. The reactions to the CV-19 crisis convinces me that humans are collectively incapable of reacting to advance warnings that involve painful sacrifices until the consequences of inactivity are irrefutable and immediate.

This makes it difficult for climbers: I strongly believe that exploratory climbing and mountaineering embody important human aspirations to transcend perceived limitations and boundaries, but at what point does the carbon footprint that this entails undermine the journey? Back in the day we were innocent of the collective toll our travels contributed to global warming. On the other hand, we could throw out the baby with the bath water, and our empty seat on the plane will be used for more mundane pursuits.

I don’t have an answer to this but my personal compromise satisfies my conscience: most of my travel is attached to hand’s on delivery that couldn’t be delegated to a local. Now that we have a global team we are increasing able to deploy experts who live closer to the training site, so as our impact has expanded, our carbon footprint has stabilised. I don’t know what the post-lockdown world will look like though. Several of our sponsors, and many of the candidates will face huge financial losses, possibly career-changing ones. On the other hand, worldwide the demand for adventure and exploring nature will increase as more communities trade farming and transhumance for city life and find their souls sickened for connection to the earth as a by-product. So I believe that the demand for training and coaching will increase, and we will find new ways to deliver it.

Steve during a training project in Jordan. Photo: Steve Long Collection

How was your big-walling trip to Brazil in 2018? Are you going back?

This was my first climbing expedition in over a decade, other than the occasional cragging trip. But this was too tempting to resist! Twid Turner’s endless quest for new rock walls had unearthed photos of a huge unclimbed face on Pedra Baiana, in the heart of Brazil. He had assembled a very strong team, including my friend Rob Johnson, who has branched out from climbing instruction into film-making. And of course we also had James Taylor and Angus Kille, who are no strangers to cranking it out on some small holds and spaced gear! The wall is raked by dozens of vertical "tramlines" for hundreds of metres, protected by what appeared to be blank granite slabs. This was breached by an obvious crackline at the righthand side of the face, so this was our goal. Our journey was an epic in itself, as the whole country had ground to a standstill due to transport strikes - however, there are worse places to be stranded than Rio de Janeiro! The crackline unfortunately proved to be guarded by millions of wasps, nesting side by side in the cracks. Free climbing the line would obviously be impossible: even placing cams soon brought a painfully clear message that the wasps would not tolerate disturbance! It was a rich experience, and Brazil should be on everybody’s "bucket list”. As with all my travels, we found the rural population to be friendly and welcoming: not the ideal destination for vegetarians though, as the youngsters soon discovered! However, I wasn’t keen to go back - the trip felt more like a boot camp than a climbing holiday! Sure, I got to lead a couple of great pitches, but there was an awful lot of hard physical labour with the constant menace of potential wasp attack. It was the sort of trip that requires a climbing holiday to get over it!

Steve during a slightly different big-walling trip with Jerry Gore jumaring on 'Sabah.' Photo: Steve Long Collection

There's a photo hanging on the wall in Plas y Brenin with your name on it. It looks like Les Drus in Chamonix. Any ideas what this could be?

I’ve been climbing regularly since 1979! Back in the day I spent every summer in the Alps, and the occasional trip further afield. I tended to be drawn to climbs or mountains that I had read about, particularly those with inspiring photos, and big walls were certainly my biggest inspiration. I free climbed three different lines on Norway’s Troll Wall while at University; of these the Swedish Route was quite tricky for the early 80’s, weighing in at about E4. Over the years I cherry picked several of the world’s classic walls, including El Capitan of course, but other standouts include the amazing Lotus Flower Tower (arguably the finest classic free climb in the world within the E2/3 level of difficulty) and the tough aid route (and much tougher free climb!) Ozymandias Direct at Mount Buffalo, Australia. Never anything cutting edge, always motivated by the line, the history etc. However, that did involve a few early or unusual repeats and the occasional new route.

The picture you’re referring to was probably my winter ascent of the French Direct on the Dru - I had witnessed the first ascent of this when climbing the American Direct. Following a winter working in Spitsbergen, combining big walls with cold conditions seemed a logical progression, and my old friend John Silvester, now of parascending fame, was up for the adventure.

The biggest and most dangerous expedition by far was an attempt on the Norweigen Pillar on Great Trango, Pakistan. This was another Twid Turner adventure, and compared to every other trip it “turned the amplifier up to 11” for all of us! I’m sure that if any of us had known just how big and serious this undertaking was we would have made our excuses at the planning stage! We survived the trip, but only just. That was when I realised that I preferred my challenges to be less out on a limb! This climb haunted me for the following year, as I spent months learning to edit videos in order to put together the raw footage that we had shot on the wall, eventually making a movie that was screened at the Kendal IMFF.

Of all the trips and adventures though, my favourite memories are from a couple of trips to Borneo, first a canyoning expedition to make the first descent of the notorious Lows Gully (older readers will remember a British Army expedition coming unstuck down there) and afterwards an ascent of the Gully’s huge side wall, again with Twid and Louise, a route that we named the Crucible. Jerry Gore and I teamed up for the first time on that climb: we spent the first few days sqabbling, but then became the firmest of friends when I realised the Jerry has a heart of gold (coincidentally the name of my favourite route on my favourite crag; the Red Walls of Gogarth).

During a winter ascent of the French Direct on Le Dru with John Silvester. Photo: Steve Long Collection

What happened on Conan the Librarian [the E6 6b at Gogarth] with Calum Muskett?

I’ve climbed quite a bit with Calum, he is of course in a completely different league as a climber, but I’m a handy belayer by now and we can swing leads on routes with bumbly approach or finishing pitches. This approach worked well up to a point - in fact that high point was undoubtedly Mister Softy (E6 6a) in Wen Zawn. A week or so later came the low point: Conan the Librarian. It’s not a huge amount more technical - when it’s dry - however on the day that we rocked up, I could see that was minging wet from the vantage point on the promontory. Of course for Calum that was no big deal; a few wet holds are no great problem if they feel like jugs to you. “How hard can it be?” said he. Pretty damned tricky, it turned out. I quickly realised that it was not my day, when the swell picked up and glubbed me, so I ended up belaying in my shreddies while drying the trousers on the rocks. Meanwhile Calum was having quite a battle up in the crux groove, which turns out to be quite problematic when the holds are covered in slime. Eventually he slapped his way out to the hanging stance above the archway. This is a spooky belay on a set of small-ish cams jammed into a horizontal crack.

In retrospect I should have congratulated him and recommended continuing up the next groove “to avoid the awkward change over” but instead I led on through. What was I thinking of?! Having shoved a cam into the same crack as the belay, I pulled into the groove and started fighting my way up it. The holds were quite big, but gopping wet. I clipped a couple of rusty pegs, and fiddled some wires into a flaky crack. Out on the left wall I could see quite a good peg, albeit with the usual rust streak decorating the rock below, however, despite my best efforts everything was too wet for me to clip it. Eventually I gave up and continued to wobble my way up the groove. I remember stretching out rightwards for a positive edge, but it sloped down to the right and like everything else was caked in slime. My hands kept sliding down the hold; it was like hanging on to an escalator. I fiddled in some more wires, but I couldn’t look properly into the crack. Eventually, gravity won - “Take!”

It’s a shame I hadn’t reached that peg, because everything else ripped or snapped! I vividly remember falling headfirst, the wall hurtling by. Twice I slowed a little as the rope came onto a cluster of gear, twice a jolt as the gear was ejected and I continued my merry way towards the sea. I passed Calum and kept going. And kept going. Finally, I remember swinging into the space below the arch, as the rope came tight on the first runner, the one in the same crack as the rest of the belay. Calum stayed remarkably calm, considering! Having put our prusiking skills to good use, Calum declined my offer to let him finish the pitch so we made a tricky diagonal abseil to escape.

Climbing out up a wet E2 on the face was a bit of an anticlimax.

I’ve climbed quite a bit with Calum, he is of course in a completely different league as a climber, but I’m a handy belayer by now and we can swing leads on routes with bumbly approach or finishing pitches. This approach worked well up to a point - in fact that high point was undoubtedly Mister Softy (E6 6a) in Wen Zawn. A week or so later came the low point: Conan the Librarian. It’s not a huge amount more technical - when it’s dry - however on the day that we rocked up, I could see that was minging wet from the vantage point on the promontory. Of course for Calum that was no big deal; a few wet holds are no great problem if they feel like jugs to you. “How hard can it be?” said he. Pretty damned tricky, it turned out. I quickly realised that it was not my day, when the swell picked up and glubbed me, so I ended up belaying in my shreddies while drying the trousers on the rocks. Meanwhile Calum was having quite a battle up in the crux groove, which turns out to be quite problematic when the holds are covered in slime. Eventually he slapped his way out to the hanging stance above the archway. This is a spooky belay on a set of small-ish cams jammed into a horizontal crack.

In retrospect I should have congratulated him and recommended continuing up the next groove “to avoid the awkward change over” but instead I led on through. What was I thinking of?! Having shoved a cam into the same crack as the belay, I pulled into the groove and started fighting my way up it. The holds were quite big, but gopping wet. I clipped a couple of rusty pegs, and fiddled some wires into a flaky crack. Out on the left wall I could see quite a good peg, albeit with the usual rust streak decorating the rock below, however, despite my best efforts everything was too wet for me to clip it. Eventually I gave up and continued to wobble my way up the groove. I remember stretching out rightwards for a positive edge, but it sloped down to the right and like everything else was caked in slime. My hands kept sliding down the hold; it was like hanging on to an escalator. I fiddled in some more wires, but I couldn’t look properly into the crack. Eventually, gravity won - “Take!”

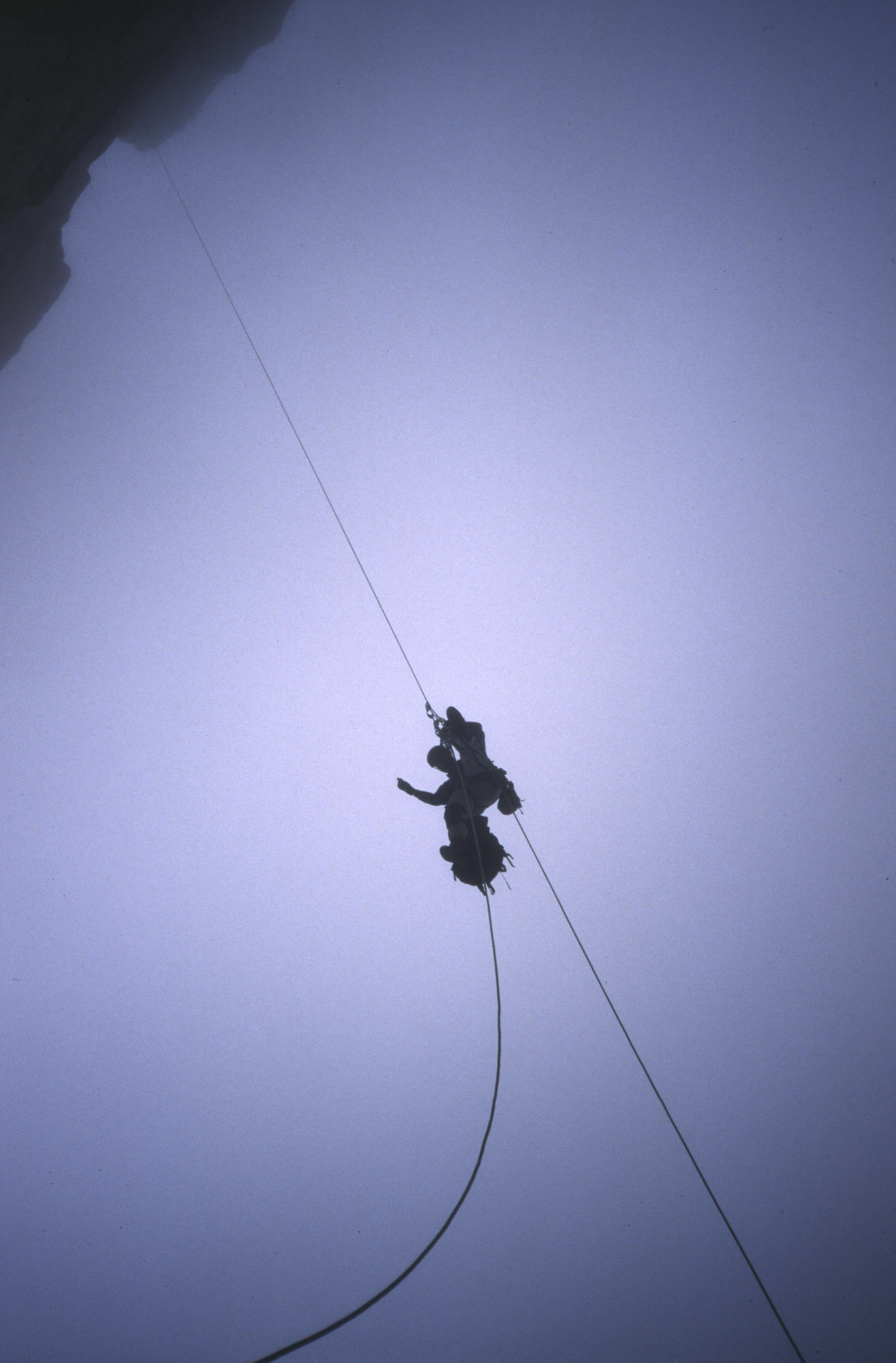

It’s a shame I hadn’t reached that peg, because everything else ripped or snapped! I vividly remember falling headfirst, the wall hurtling by. Twice I slowed a little as the rope came onto a cluster of gear, twice a jolt as the gear was ejected and I continued my merry way towards the sea. I passed Calum and kept going. And kept going. Finally, I remember swinging into the space below the arch, as the rope came tight on the first runner, the one in the same crack as the rest of the belay. Calum stayed remarkably calm, considering! Having put our prusiking skills to good use, Calum declined my offer to let him finish the pitch so we made a tricky diagonal abseil to escape.

Climbing out up a wet E2 on the face was a bit of an anticlimax.

Steve prussiking up his ropes after the fall on Conan. Photo: Calum Muskett

Finally, who would you pass the time with on a belay ledge?

Well, that depends a bit on the situation. If it needed somebody with enough ability and compassion to get me out of a tricky situation in one piece it would probably need to be Calum if that required more climbing to escape the ledge. For shooting the breeze, it might be Jerry Gore, as I can spend weeks ripping the piss out of him. I’m not going to risk a celebrity because that would require a dinner party in order to break the ice. I’ve got a ready made list for that; we drew up a list after several beers after a UIAA meeting in Slovenia!

I wouldn’t want to inflict it on my wife, because she hates climbing with a passion! I think John Long would be a good candidate - he’s led a really adventurous life and has a brilliant way with words. Maybe Cesare Maestri, if there might be a chance of wheedling the truth out of him about what really happened on Cerro Torre. I was stuck on a ledge for a week once, with Louise Thomas and she was the perfect partner, along with Twid and Steve Meyers, who were also there.

Steve leading on the Lotus Flower Tower, Canada. Photo: Steve Long Collection